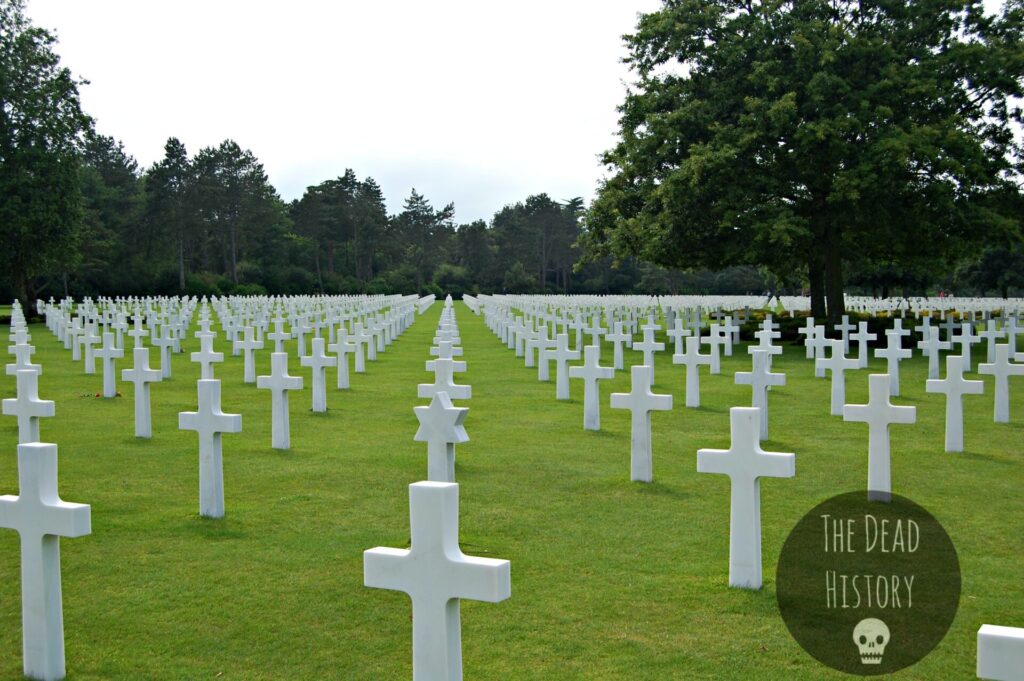

I received a request to research Mouth Cemetery, and I’m not going to lie, I got a little excited because what a name for a cemetery! Turns out the name is based on geographical location and not something quirky. Despite this, after doing a bit of research, I discovered that Mouth Cemetery Hauntings have made this remote graveyard one of Michigan’s most eerie locations. The cemetery and surrounding area have a long history of strange occurrences. Mouth Cemetery sits in White River Township, Michigan, near the shores of Lake Michigan. Surrounded by dense trees, its secluded setting only adds to its haunted reputation.

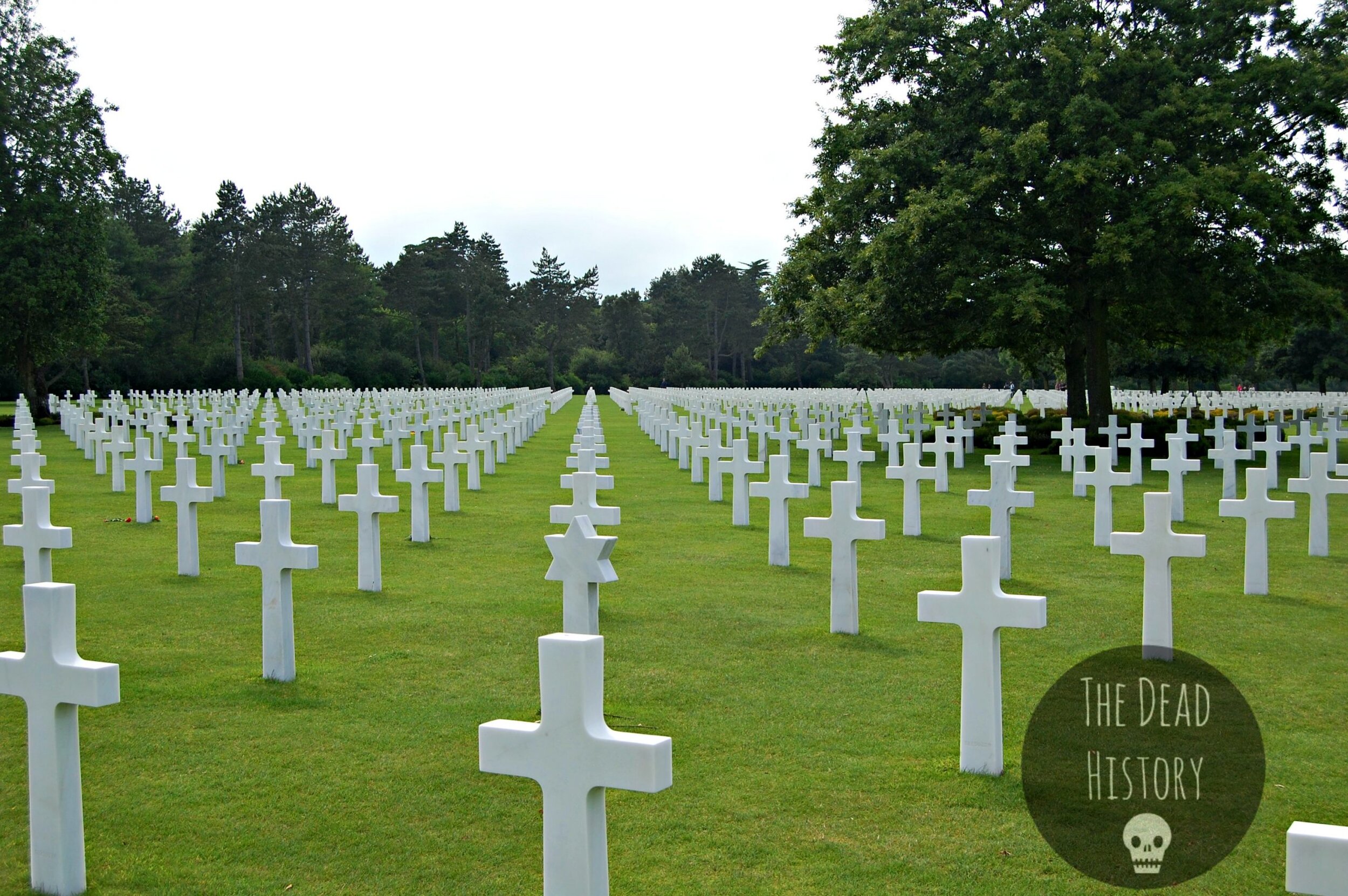

At over 165 years old, Mouth Cemetery has fallen into disrepair and appears mostly overgrown. Based on its remoteness and unkempt appearance, it’s not hard to see how this cemetery has gained the reputation of being one of Michigan’s most haunted locations. Visitors to the cemetery have reported seeing strange mists among the bushes and trees. They also hear the sound of footsteps behind them yet turn and find no one. They have also reported seeing a young girl in an old-fashioned white dress and hearing disembodied sounds of crying and screams. As if all of that wasn’t enough, there is also an urban legend connected to Mouth Cemetery, the cursed chair!

With a name like Mouth….

Located near the mouth of the White River, in White River Township, Mouth cemetery got its name from an old town nickname. Locally the town was often referred to as “the Mouth” or simply “Mouth”. The nickname stuck for the cemetery and also one of its first schools. Long before White River Township existed, there was a large Native American village at the mouth of the White River. According to stories passed down through the years and a few historical records, a great massacre between tribes occurred on the north shore of White Lake in the mid-1600’s. This event most likely occurred during the Beaver Wars.

In 1854, officials established the White River Village post office, and the town thrived as a lumber hub. The earliest tombstone in the cemetery dates to 1851, though historians believe burials began around 1830. In 1859, city officials burned all township records, making it impossible to reconcile the financial accounts. In doing so, they also destroyed all early burial records for Mouth Cemetery.

Spectral Lightkeeper

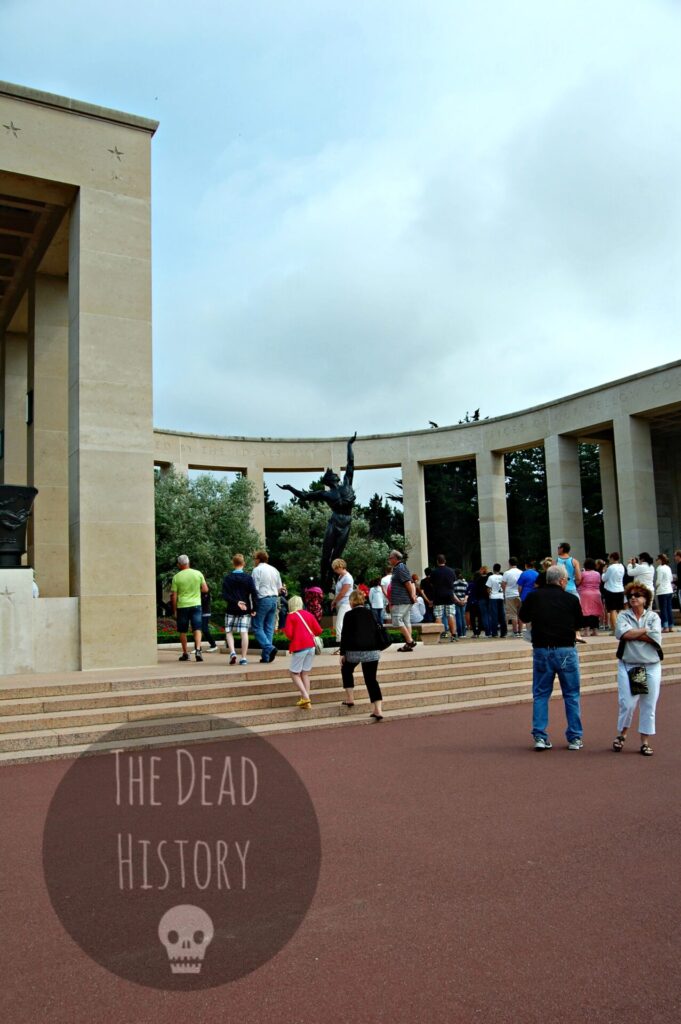

Time has erased many names at Mouth Cemetery, but one grave still sparks conversation—Captain William Robinson’s. Interestingly, people report seeing and hearing his ghost, not at Mouth Cemetery, but at the nearby White River Light Station. Witnesses claim both Captain Robinson and his wife, Sara, haunt the lighthouse.

Captain Robinson became the lighthouse keeper when it opened in 1875 and maintained the post for 45 years until he died in 1919. At 87, he refused to retire, but authorities eventually forced him to step down due to his age. His grandson took over his duties, but many believed the heartbreak of leaving the lighthouse hastened Robinson’s death. He passed away the day before he was set to leave.

After closing for the night, staff at the White River Light Station hear footsteps and the distinct thunk of a cane echoing through the building. Towards the end of his life, Captain Robinson used a cane to get around. I found mentions of the sounds of his distinct gait. It doesn’t seem that Captain Robinson is alone at the lighthouse, however. Museum staff report seeing dust rags move on their own when left near a specific display case after visiting hours.

While many believe Captain Robinson’s spirit lingers at the lighthouse instead of his grave, Mouth Cemetery holds its own dark lore. Among the many eerie encounters reported by visitors, one story stands out for its chilling reputation — the legend of the cursed chair.

The Mouth Cemetery Hauntings

Many consider Mouth Cemetery one of the most haunted cemeteries in Michigan, and it also holds an eerie urban legend. A teenage boy who sat in a chair in the woods near the cemetery reportedly died in a car accident exactly one year later, according to the Grand Rapids Paranormal Investigations blog. People also call it Sadony’s chair, but we’ll get to that later. So many visitors flocked to the cemetery because of the cursed chair legend that local police removed it. Whether they did this to prevent vandalism or to silence the legend remains a mystery.

Valley of The Pines & Joseph A. Sadony

If Mouth Cemetery wasn’t already eerie enough, it lies near the former estate of one of Michigan’s most enigmatic figures, Joseph A. Sadony. Known as a ‘philosopher-scientist,’ Sadony dedicated his life to studying intuition. He also reportedly possessed an uncanny ability to foresee future events—including his own death. To call him merely interesting greatly understates his fascinating character.

When I first started researching the cemetery I couldn’t understand the connection to Joseph Sadony or events that occurred nearby at his estate, Valley of The Pines to Mouth Cemetery. He died in 1960 and is buried at Valley of The Pines. I read numerous newspaper articles printed during his lifetime about him and Valley of The Pines. I also read many different current websites about his life and beliefs. Most of the articles written about him were very positive. A few articles referred to Valley of The Pines as a cult and painted a less than flattering picture of Joseph Sadony. It was then that I realized that his name is mentioned in connection to Mouth Cemetery. He lived close to the cemetery and was considered a very unusual person.

Legends, Lore, and the Power of the Unexplained

Over the years of researching haunted locations and urban legends, I’ve found that even just a little bit of weirdness is often enough to spark an urban legend. Even if he had lived today he would be considered unusual and different. This was especially true during his lifetime (1877-1960). In an interview with his granddaughter, she mentioned how her father told her that people would often see Joseph Sadony walking down the street. They would cross to the other side to avoid getting too close. They were afraid that he could read their minds.

The proximity of the mysterious Valley of The Pines — where Sadony kept his laboratory and wrote his newspaper columns — only added to the eerie lore surrounding the cemetery.

Do you know of a great urban legend or a haunted location that you’d like to learn the real history of? Send me the info and it could be featured in a future Dead History post.

Sources

- http://www.genealogymuskegon.com/Databases/Cemeteries/Mouth/mouth.htm

- Detroit Free Press, Sun, Jan 16, 1994

- http://absolutemichigan.com/michigan/still-on-duty-at-white-river-light/

- http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=192

- http://www.coastalliving.com/travel/top-15-haunted-lighthouses/haunted-lighthouses-white-river-light-station