At the corner of Ivar and Hollywood, just behind the frantic pulse of the Walk of Fame, sits the Knickerbocker. What started as an upscale residence in the 1920s later became a hotel, then finally a retirement home. The sign still clings to the roof, faded but proud. If you blink, you might miss it. But the stories wait for you.

Hollywood history soaked into the walls here. You’ll find stories of movie stars and suicides, séances and scandals. The Knickerbocker isn’t just haunted. It’s Hollywood haunted. A place where tragedy and fame share the same mirror. And the ghosts, if they’re here, don’t seem eager to leave.

D.W. Griffith: A Ghost of Hollywood’s Making

“David Wark Griffith, 73, pioneer film director, whose photoplay The Birth of a Nation gave Hollywood its start as the world’s movie capital, died at 8:24 a.m. today in Temple Hospital after he was stricken in his room in the Hollywood Knickerbocker Hotel yesterday.”

That’s how the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News announced it on July 23, 1948. There was no mention of The Birth of a Nation’s legacy. No mention of the protests that followed its release. Or of how Griffith’s most famous film helped shape the visual tools of American white supremacy.

It was the first movie screened at the White House. President Woodrow Wilson reportedly said it was “like writing history with lightning.” Whether or not he said it, the effect was the same. The film glorified the Ku Klux Klan, villainized Black Americans, and used white actors in blackface. It wasn’t just a movie. It was propaganda. And it worked.

Griffith made history, then outlived it. He pushed film forward, but not always for good. By the time he moved into the Knickerbocker, he was mostly forgotten. The phone didn’t ring anymore. His death was quiet. He died alone in his apartment, not the lobby.

Some guests and residents have claimed to see an older man with a cane, dressed in early 20th-century fashion, walking the halls and humming to himself. When they take a second look, he’s gone. If his ghost remains, it doesn’t bring comfort. It’s a reminder. Griffith changed film forever, but he used that power to push a dangerous lie. The past isn’t always something to celebrate. Sometimes it just lingers.

Frances Farmer: The Woman in the Hall

On January 13, 1943, actress Frances Farmer was arrested inside her room at the Knickerbocker. She had locked herself in, refused to answer the door or phone, and reportedly struck a hotel busboy with a lamp. When police arrived, she fled to the bathroom. She reemerged naked, shouting lines from her films, and was subdued only after officers removed her shoes to stop her from kicking them.

This is where the legend takes over.

Most ghost stories claim she was dragged naked through the lobby, or wrapped in a shower curtain, screaming the whole way. But the truth is different. Once she calmed, police allowed her to dress. She chose a powder blue wool suit. She was handcuffed and taken not so quietly to jail.

Farmer had been arrested weeks earlier for drunk driving. Frances hadn’t paid her fine. She hadn’t followed the terms of her probation. And she had also been accused of assaulting a hairdresser on set. Her career unraveled as her behavior grew more erratic. Eventually, she would be institutionalized and diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Her story was tabloid gold. No one cared that she was sick.

Frances died in 1970 from throat cancer. She was 56.

Some say she still walks the halls of the Knickerbocker, barefoot, angry, echoing with loss. But maybe what people feel isn’t a haunting. Maybe it’s guilt. She was mocked, used, discarded. Her ghost, if it’s here, holds up a mirror.

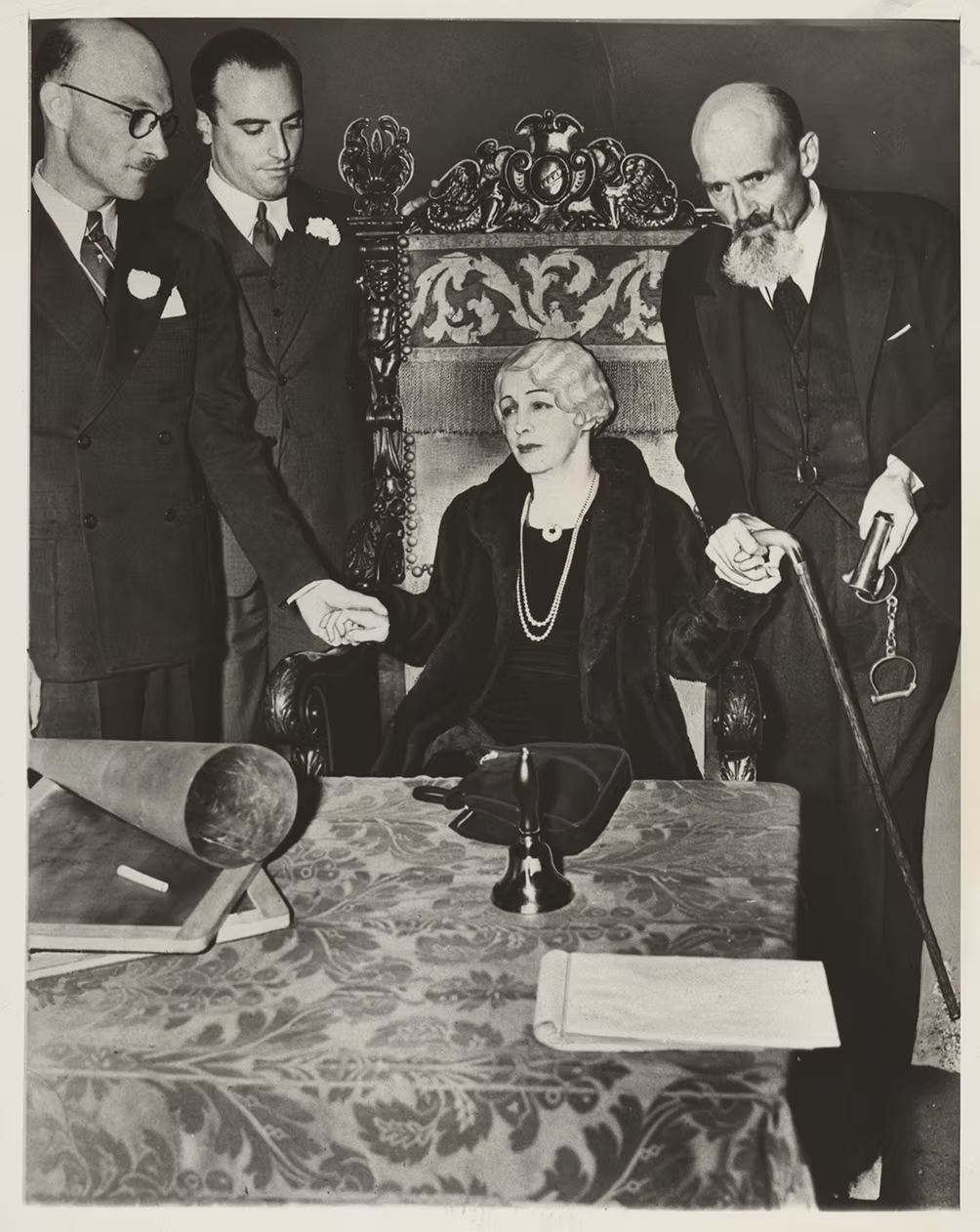

Bess Houdini and the Final Séance

In October 1936, Bess Houdini checked into the Knickerbocker Hotel. She had one goal, to keep a promise.

A decade earlier, her husband, Harry Houdini, had died. Before his death, the couple made a pact. If it was possible to come back, Houdini would find a way. For ten years, Bess waited. Each Halloween, she held a séance. In 1936, the deadline approached.

On Halloween night, Bess and a small group gathered on the hotel’s rooftop. They placed Houdini’s handcuffs in a circle and lit a ruby-colored candle. If the cuffs opened, it would be a sign. They didn’t. Others around the world joined in, hoping for a signal. None came.

The next morning, Bess held a press conference from her room. She ended it with this:

“Houdini could escape anything alive. If he cannot escape from the ‘other side’ in ten years, then I cannot believe that anyone can.”

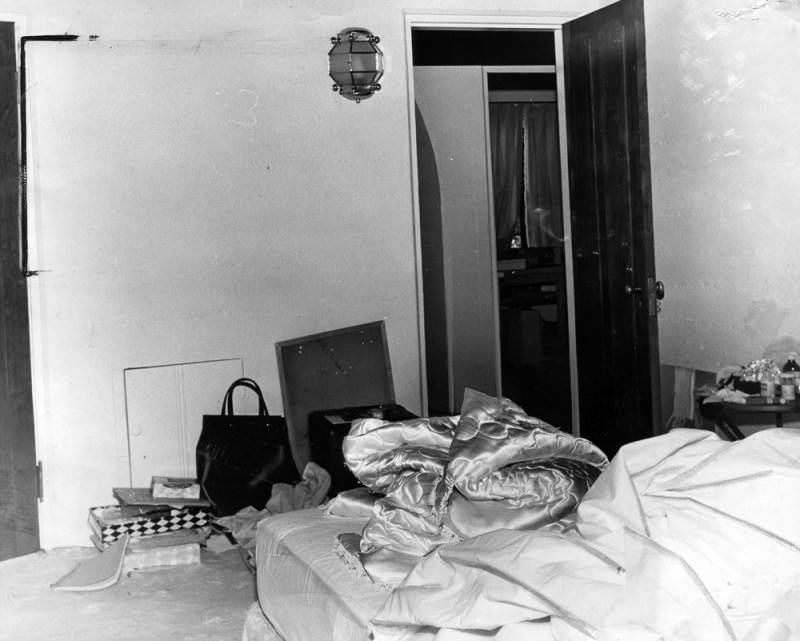

Irene Lentz: The Fall

On November 15, 1962, Irene Lentz Gibbons checked into the Knickerbocker Hotel and was given Room 1129. She wasn’t just anyone. Irene had dressed the most famous women in Hollywood: Marlene Dietrich, Rosalind Russell, and Ingrid Bergman. She had built a name designing elegance. Even after she left MGM, movie stars kept coming to her.

Days before her death, Irene’s designs were on display at the California Fashion Show in Beverly Hills. She gave an interview. “Anything new and beautiful makes one think beautiful thoughts,” she said. But behind the beauty, she was unraveling.

She had returned to work after a long break. Her husband, Eliot Gibbons, had recently suffered a stroke. The stress had taken its toll. Her firm’s general manager, Alden Olds, said she had been in poor health for two years. “She was a stalwart girl with a great deal of love for life,” he said. “And this thing was just too much for her to bear.”

What the Papers Didn’t Say

In the bathroom of her hotel room, she tried to end her life by slitting her wrists. When that didn’t work, she opened the window in her eleventh-floor room and jumped. Her body landed on the roof over the hotel lobby.

She left several suicide notes. One was to her neighbors in the hotel. “Sorry I had to drink so much to get courage to do this,” she wrote. Another note asked that her husband be cared for. She also wrote, “Get someone very good to design and be happy. I love you all. Irene.”

In one of her last conversations, Irene told her friend Doris Day that Gary Cooper was the only man she ever truly loved. He had died a little over a year earlier.

Following her death, rumors began to emerge that her spirit lingers. Some feel a cold spot near the window. Others say they see a woman in period clothing standing at the sill. The most chilling stories describe her fall repeating itself. Over and over. Just until she disappears.

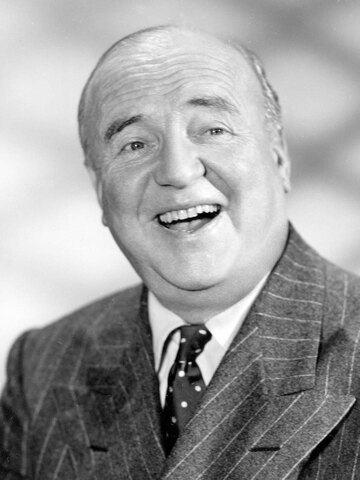

William Frawley: Buried Truths

People like to say William Frawley died in the lobby of the Knickerbocker. Maybe it’s the Hollywood setting. Maybe it’s because he played Fred Mertz on I Love Lucy, and the idea of him dropping dead in a hotel lobby feels like the perfect closing gag.

But it didn’t happen that way.

While Frawley had indeed lived in an apartment in the Knickerbocker Hotel for many years, for the last few months prior to his death he had been living in the nearby El Royale. On March 3, 1966, he left a movie theater, collapsed on the sidewalk near Ivar and Hollywood, and never got back up. A nurse on the scene tried to help to no avail. He was taken to Hollywood Receiving Hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

There’s no record of his ghost haunting the Knickerbocker. The lobby just became part of the story. An accidental set for a death that didn’t happen there. Maybe it’s easier to imagine him going out with an audience.

Roger the Bellhop: Fiction and Folklore

If you’ve heard of a ghostly bellhop named Roger wandering the Knickerbocker, you’re not alone. Some say he waits by the elevator. Some say the doors open for him.

Regardless, the earliest mention of Roger comes from David Fisher, who ran the All Star Theatre Café and Speakeasy out of the old hotel lounge in the 1990s. Fisher, who also went by Max, had a gift for stories. He said the bar was haunted by Rudolph Valentino. That Monroe still stared into the mirror in the ladies’ room. That the front door slammed shut for no reason. That Roger’s body sometimes floated past.

And he even claimed the bar closed in the late 1960s because of all the ghosts.

Maybe Roger the bellhop really did stick around. Or maybe he was born from decades of rumors and candlelit talk. There’s no record of him. No sightings before Max. Just stories.But that doesn’t mean people didn’t believe. Some still do.

Shep: The Elevator Dog

Before he was a ghost, he was just a good boy.

In the 1940s, an English Setter named Shep lived at the Knickerbocker Hotel. His owner, Jack Matthews, the hotel’s manager, taught him elevator etiquette. Shep could press the buzzer with his paw. If there were ladies waiting, he’d let them board first. If not, he’d go in alone and ride to his floor like any other guest.

Locals loved him. He was part of the building’s daily rhythm. Guests chatted with him. Kids followed him around. He even made the papers.

In the years following Shep’s death reports of a ghostly dog began to surface. Some saw a flash of white fur rounding the corner. Others heard soft paws on the hallway carpet. A few felt the brush of something warm and gentle at their side.

Some stories call him Speck. But his name was Shep, and even in death he’s still a good boy.

Marilyn Monroe and the Ghost of Glamour

I think it’s safe to say that most people know where Marilyn Monroe died on August 4th, 1962. It wasn’t the Knickerbocker Hotel. And while Marilyn’s ghost is said to appear in a bunch of different places, it is true that she spent some happier times at the Knickerbocker.

It was here that she met Joe DiMaggio’s family. Picked him up from the hotel. Drove him to the airport. Stayed at his apartment in the hotel, spent time at the bar. The press couldn’t get enough. They called her hair wild and her smile perfect. They said she and Joe couldn’t stay married, but they couldn’t stay apart either.

Stories and legend place her ghost in the ladies’ room, staring at her reflection. They see her seated at the bar, lipstick smudged on a phantom glass. It should come as no surprise that Marilyn Monroe’s ghost is one of the most frequently reported in Hollywood. Whether it’s memory, myth, or something stranger, people still say she hasn’t left.

Final Word

The Knickerbocker isn’t a haunted attraction. It’s not a museum. It’s just a building full of memory. Some of it is true. Some of it isn’t. All of it matters. By 1970, the hotel had seen its last Hollywood heyday. The neighborhood changed. The guests did too. That year, the Knickerbocker was converted into a retirement home. It still is today.

Truly life is weird, wonderful and surprising in Hollywood.

What do you think? Can a building hold on to sorrow, glamour, and memory all at once? Have you ever felt a chill in a place that wasn’t cold, or seen something just out of the corner of your eye that shouldn’t be there?

Historical and Newspaper Sources (Primary):

- Los Angeles Evening Citizen News

- Los Angeles Times

- LA Weekly

- The Hollywood Reporter

- The Daily News (6/13/1945 — Shep the dog)

Paranormal & Haunting Coverage:

- Los Angeles Times – “Some of L.A.’s Most Famous Haunts” (1999)

- LA Mag – Knickerbocker Hotel Ghost Stories

- Stronghold Nation – Haunted Knickerbocker Hotel

- Curbed LA – Haunted Hotels in Los Angeles

- The Haunted States – Knickerbocker

- PBS SoCal – Haunted History of the Knickerbocker

- Skeptical Inquirer – Ghost Investigations at the Knickerbocker

- LA Ghost Tour – Knickerbocker