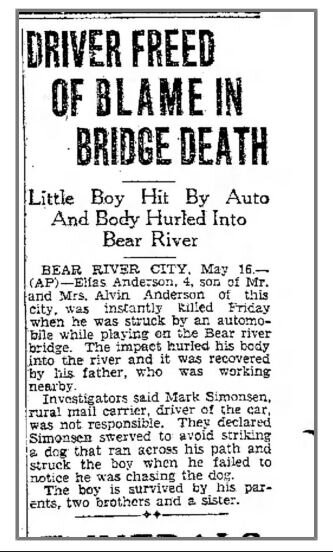

There’s a legend surrounding Whiskey Pete’s Hotel & Casino in Primm, Nevada that says the place is haunted by old Whiskey Pete himself. Patrons and staff alike have reported the unnerving feeling of being watched. As they look around they spot an elderly man wearing old fashioned western wear who then promptly vanishes before their eyes. The legend says that Pete still haunts his former property because his grave was disturbed during the construction of the resort, and he wants everyone to know that he’s still around keeping an eye on things.

I had heard of this legend before, and honestly, I chalked it all up to be a legend because there are never any details to the reports such as who saw the ghost and when. On top of that, I didn’t realize that Whiskey Pete was even a real person and it all just sounded too much like an urban legend to me. But, as it turns out, Whiskey Pete was a real person and his grave was actually disturbed.

The Beginnings of Whiskey Pete

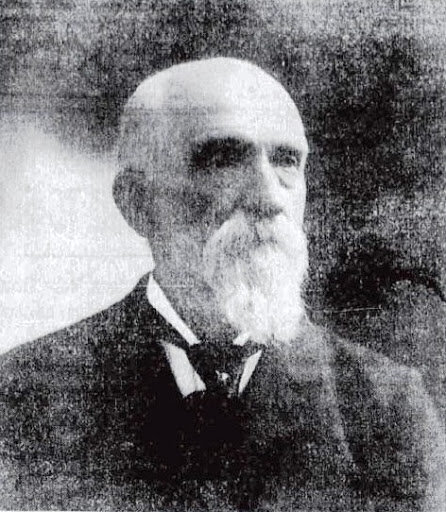

Long before the hotels that straddle the freeway in Primm, Nevada sat a small service station called the State Line Station, which was run by a cantankerous moonshiner named Pete McIntyre. Most people in the area knew him as Whiskey Pete, and it seems like Pete was the type of guy who took no crap from anyone! Pete was very well known in Las Vegas and there were a few who did not care for him much and felt that he could get away with anything.

Pete is a difficult guy to trace through historical records. He does not show up in the 1900, 1910, or 1920 U.S. Census that I can find. He does show up in the Tulare County jail, however, in January 1918. He was arrested for running a “blind pig” otherwise known as a speakeasy. While he was eventually sentenced to 30 days in jail, he actually served a little over two months because he could not make bail initially. His place of birth listed is Arizona, which differs from where he would list his place of birth in the 1930 Census. The jail records state his occupation was a miner. In 1922 he was again arrested for bootlegging, this time in Nevada, and spent 6 months in jail.

He’s first listed on the 1930 U.S. Census living in Crescent, Nevada, a small mining town near the Nevada California line. He lists his occupation as the proprietor of a service station. He’s first mentioned in the Las Vegas newspapers in 1928 when the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce read a letter from a woman who stopped at Whiskey Pete’s gas station. According to the woman it was about 11 p.m. and she stopped to have her oil and water checked and to get gas. Whiskey Pete came out to serve them and when he realized that the car only needed water he became “abusive and threatening and refused to let them have water.” He forced the woman to drive to the next service station with an empty radiator and an overheated engine. The Chamber of Commerce said that for months they had received similar complaints from tourists driving to and from Las Vegas to California. One of the complaints said that Whiskey Pete shot at them and another said he threatened to shoot them. They referred the information to the Las Vegas sheriff so that he could have a chat with Pete.

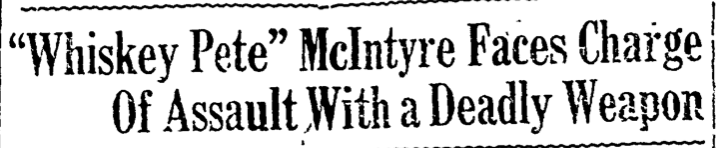

Pete’s attitude might have chilled out for a bit but by March 1931 Pete was facing a charge of assault with a deadly weapon for shooting the Elgin postmaster, Rube Bradshaw in the shoulder. Unsurprisingly the two men had different versions of what happened. According to Rube, he stopped at the gas station with his two sons and when he walked inside Pete was already “surly”. When he asked Pete for a cup of coffee he said Pete became enraged so he simply said he’d get his coffee elsewhere and started to leave. When he reached the door he said that Pete called him a “vile name” and when he turned around to face him, Pete shot him in the shoulder with a pistol.

A preliminary hearing was set for Pete at which he pleaded not guilty and was released on bail. Pete told the reporters that he resented the bad reputation he had and that his remote location makes it necessary for him to be armed at all times. He also made sure to let the reporters know that he was paying for all of Rube Bradshaw’s hospital and medical expenses. Eventually, the charges against Pete were dropped when Bradshaw failed to show at court three separate times.

At some point in early 1932, Pete married a woman named Lauretta Frances Enders. By October she had apparently had enough and took him to court on charges of insanity. According to physicians Pete was just fine mentally, but physically he was likely to die in a matter of days due to “miner’s consumption.” Mrs. McIntyre was the only witness against her husband and claimed that he would “fly into a rage every time he sees me and accuses me of all sorts of things.” Pete quickly admitted to flying into rages but added: “who wouldn’t when they find their wife running around naked in the hills with other men.”

He said that a few weeks prior, Lauretta took him to the Stillwell Sanitarium in Banning, Calfornia and remained there with him, helping to care for him. As soon as he showed signs of recovering she left him. Lauretta was supposed to be looking after the service station, but when he was well enough to go home he found she hadn’t paid attention to it at all and was “running around with other men.” The judge denied Laurett’s motion to have him committed and there is really no mention of her after this.

By December of 1932, Pete declared that he was too busy to die and that he was now four months past his funeral date. By September of 1933, Pete was living back at Stillwell where he told reporters he was doing okay. Whiskey Pete McIntyre died on the 11th of November, 1933. It was soon announced that his funeral was to be held in Las Vegas, and this is where things get weird.

Buried Standing Up

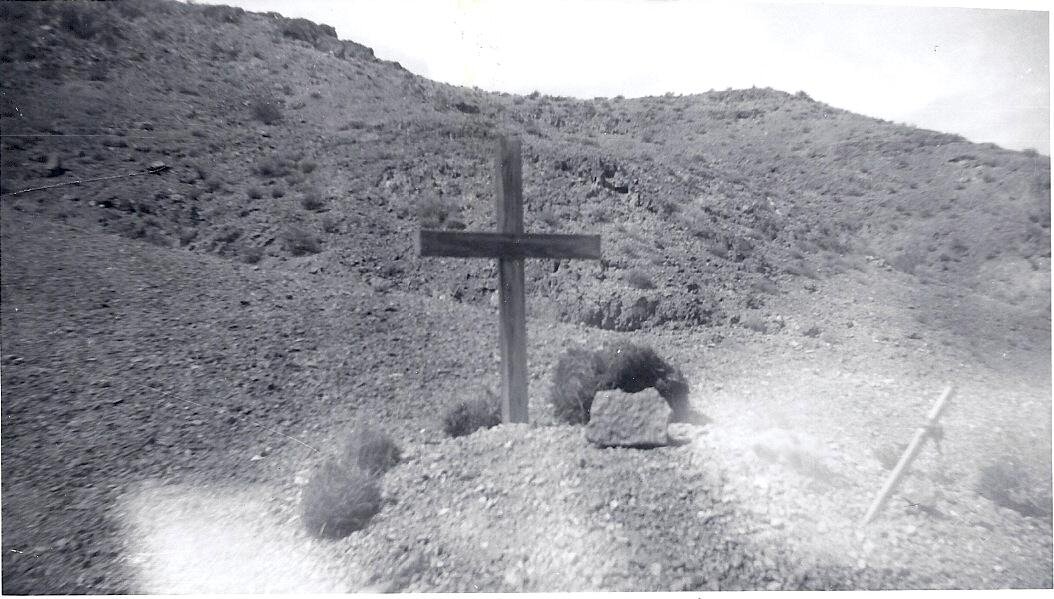

At some point prior to his death, Pete told his friends that he wanted to be buried standing up near his service station. His exact words were “Bury me up on the hill, standing up facing the valley so I can see all those sons of bitches goin’ by.” His friends did as he asked and used dynamite to blast a 6′ hole in the limestone cliff overlooking Highway 91 from behind his service station. Over the years Pete’s grave became lost to time. People repeatedly stole his grave marker until it simply wasn’t replaced. His service station was sold a few times until the location was eventually developed into Whiskey Pete’s Casino in 1977.

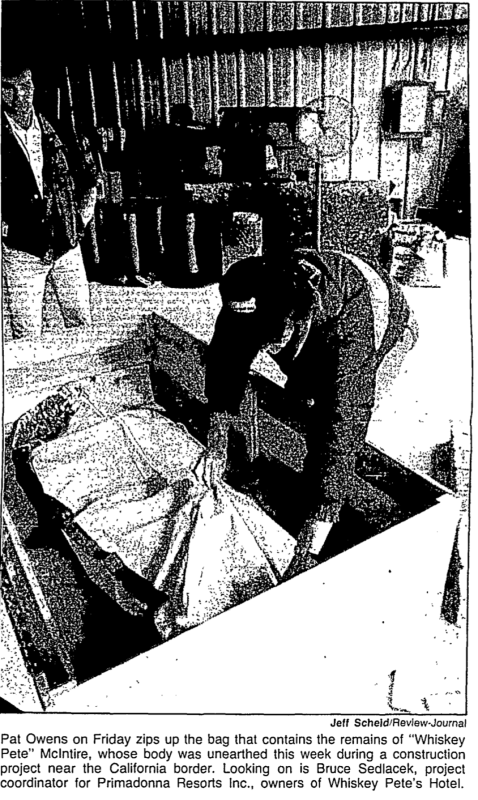

On February 2, 1994, construction workers were grading land for a railroad track that would connect Whiskey Pete’s to Buffalo Bill’s on the other side of the freeway. While working near the original site of State Line Station, they struck a crumbling wooden coffin. Inside they found the skeletal remains of Whiskey Pete himself. Even though some of the legends said he was buried with a 10-gallon hat on his head, his six-shooters strapped to his side and a jug of whiskey, all they found was his bones. He had a little bit of hair left on his skull, dentures in his mouth, and a couple of buttons left on his shirt.[mfn]Remains of Whiskey Pete found -Las Vegas Review-Journal – February 5, 1994[/mfn]

Pete’s coffin was said to be about 80% intact and buried at an angle to the highway. The project manager said they knew that Whiskey Pete was buried somewhere in the area, but they had no way of knowing exactly where. “The tractor caught the edge of the box and the skull popped out. There was Whiskey Pete staring at us.”

Although the resort said that Whiskey Pete would be reburied somewhere on the property with a memorial, it doesn’t appear that any memorial has been set up, and it’s unknown exactly where Pete has been buried. It’s rumored that his remains were reinterred in one of the caves he used to make his moonshine.