In January 1897, someone discovered Elva Zona Heaster Shue dead in her home near Livesay’s Mill, West Virginia. She was twenty-three years old. Her death was unexpected. Her husband of less than four months said it was heart failure. Her mother believed it was murder.

What followed became one of the strangest trials in American legal history. Not because of the crime, or the evidence, or the verdict. But because the testimony that led to justice didn’t come from a witness. It came, according to one woman, from a ghost.

Most people today know the legend of The Greenbrier Ghost. Zona’s community documented the case thoroughly and fought hard for justice when the system nearly failed.This wasn’t just folklore. It was a full criminal investigation, and it left behind a paper trail thick enough to follow from the crime scene to the courtroom.

This is the real story of the Greenbrier Ghost.

A Sudden Death

Zona had married Erasmus Stribbling “Trout” Shue just three months earlier, in October 1896. It was a quick courtship, and she had recently moved with him to Richlands, where he worked as a blacksmith. On the morning of Saturday, January 23, 1897, Shue made a visit to the nearby home of “Aunt Martha” Jones, a Black woman who lived close to the shop. He asked if her son, Anderson, could come by the house to help with a few chores and take some eggs to the store for Zona. Anderson, was around eleven years old.

Shue returned to the Jones household several times that morning, checking whether the boy had gone yet. He said he wouldn’t be going home for lunch and wanted Anderson to make sure Zona was all right. By the fourth visit, Anderson agreed to go.

When the boy arrived at the Shue home around 11 o’clock, he found the front door closed and the house silent. Inside, he discovered Zona’s body at the foot of the stairs in the dining room, lying face up with one arm at her side and the other stretched out. Her eyes were wide open. Her legs were straight and close together. He later said he had never seen anyone dead before, but he knew right away she was gone.

A Body Prepared Too Soon

Dr. George W. Knapp, who had treated Zona in the weeks before her death, arrived later that day. By then, Shue had already washed and dressed the body in a high-necked gown and tied a veil under her chin. This is interesting for a few different reasons. First, it would have been highly unusual for a man at the time to dress the body. In 1890s rural West Virginia, women typically prepared bodies for burial, especially in small, tight-knit communities.

When someone died at home, it was local women, often neighbors or family, who handled the washing, dressing, and laying out of the body for viewing. So for Trout Shue to insist on dressing Zona himself it would have raised a couple of red flags. Most considered it improper for a man, even a husband, to handle a deceased woman’s body in such an intimate and ritualized way, especially without assistance. It also denied the community (including her family) their expected role in mourning and preparation which further isolated the body from scrutiny. And finally, it gave Trout total control over what others would see.

What He Chose to Hide

Additionally the newspaper reports from the time state that he added a large veil which he “folded several times and tied in a large bow beneath her chin.” He never left her side. His behavior swung between loud weeping and sudden outbursts. At one point, he cradled Zona’s head and sobbed uncontrollably. Trout also “had requested Dr. Knapp, after he had resorted to the usual means of resuscitation, to make no further examination of the body.”1Greenbrier Independent 7/01/1897

Dr. Knapp recorded heart failure as the cause of death. Authorities did not order an inquest. Two days later, the family buried Zona in Soule Chapel cemetery.

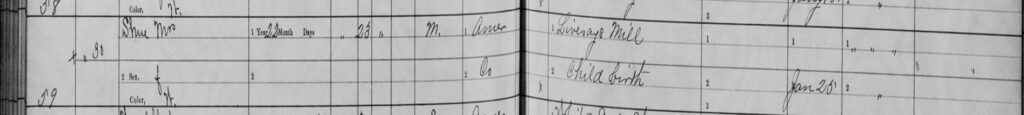

One Line in a Ledger

There was another part of Zona’s story that few talked about openly. On November 29, 1895, more than a year before her death, Zona Heaster gave birth to a baby boy. She was not married. A clerk entered the father’s name in the Greenbrier County birth ledger: George Wooldridge, who oral history says lived nearby. The Wooldridge family gave the child their surname and, according to family accounts, raised him as their own.

There is no mention of the child in any newspaper article about Zona’s death. Not in 1897, not during the trial, not in any public court record. The child disappeared from public view almost as quickly as he appeared.

But in the birth ledger, there is a mark, a small, deliberate “X” beside Zona’s name. It is the only entry on the page with such a mark. The column does not explain what the symbol means. It may have signified illegitimacy. It may have been a clerk’s quiet judgment. It may have simply been a way to set the line apart. But in that moment, someone chose to draw attention to it.

A Second Look at the Cause

When Zona died suddenly on January 23, 1897, Dr. George W. Knapp arrived to find her already dressed and laid out by her husband. He later said Trout was acting strangely. Clutching Zona’s body, refusing to let him really examiner her at all. Knapp said he couldn’t perform a full exam, so he chalked the death up to “heart failure,” a vague and convenient diagnosis that ended the matter. Or so it seemed.

The funeral happened quickly. The county clerk recorded that Zona’s family buried her two days later on January 25, 1897. But behind the scenes, something changed. On January 30, Dr Knapp filed the official return, not with “heart failure,” but with a different cause: childbirth. That word never appeared in the newspapers. Neither the prosecution nor the defense mentioned childbirth during Trout’s trial.

Whether Zona had recently miscarried or given birth again, we don’t know. But Knapp clearly suspected something serious. In the record books, there is only one line to explain how a healthy young woman died without warning. It reads: Childbirth. Dr. Knapp recorded only one official conclusion. According to that account, Zona Heaster Shue died quiestly, without violence, at home. But Zona’s neighbors didn’t believe it. Neither did her mother.

A Mother Begins to Doubt

Fourteen miles away in Meadow Bluff, Mary Heaster sat with the news that her only daughter had died without warning. Zona had not seemed in danger. There had been no last visit, no goodbye. Mary tried to accept the official story, she just couldn’t.

She had never trusted Trout Shue. Now, with Zona gone, his name filled her with suspicion, so she began to pray. And over the course of four nights, she said her daughter came to her. Not in a dream, but standing beside her bed, speaking plainly. Zona said that Shue flew into a rage when she didn’t prepare meat for dinner. He had grabbed her by the neck and snapped it.

Zona described the house in detail, rooms, furniture, even a bloodstained spot near a loose floorboard. What makes this remarkable is that Mary had never visited Zona’s house. Yet she said she found it exactly as Zona had described.

Whether or not the prosecutor believed in ghosts, the specifics of Mary Jane’s story moved him to act.

The Exhumation

On February 22, 1897, county officials exhumed Zona’s body from her grave near Little Sewell Mountain, nearly a month after her burial. Some later sources claimed she was buried at Soule Chapel Cemetery, but contemporary records and newspaper reports placed her original grave near her father’s home in the Meadow Bluff District. The confusion likely arose from the proximity of the Nickell schoolhouse, where the autopsy took place, to the Soule Chapel Church.

The order to exhume the body came after Mary Jane Heaster and her brother-in-law Johnson Heaster brought their concerns to John A. Preston, Greenbrier County’s prosecuting attorney. Mary Jane described the visions she said had come to her over four nights, waking encounters in which Zona’s spirit spoke clearly, naming her killer and describing the injuries she had suffered. Preston listened, not just to the claim of a ghost, but to the physical specifics: the broken neck, the food she said she had prepared, and the details of the house Mary Jane had never seen.

Preston believed the evidence warranted action. He ordered the exhumation and a full postmortem.

The examiners did not inspect the body at the gravesite. Instead, they brought Zona’s coffin to the nearby Nickell schoolhouse, a small one-room building near Soul Chapel Church.

What the Body Revealed

The inquest was overseen by Justice Homer McClung and a jury of inquest. The physicians conducting the examination were Dr George W. Knapp, who had attended Zona during her final illness; Dr. J.M. Rupert, and Dr. H.R. McClung. Trout Shue was summoned to attend. He reportedly stood nearby, silent and tense, as the doctors began their work.

What they found confirmed the worst. Zona’s neck had been broken. The dislocation between the first and second vertebrae was so complete that her head moved freely. Her windpipe had been crushed, and there were deep bruises across her neck and chest. The cause of death was not heart failure. It was manual violence.

The jury ruled that Zona Heaster Shue had been murdered. Trout Shue was arrested that same day and taken to jail in Lewisburg. He would await the action of the grand jury, and face the court not only for what he had done, but for what Zona’s mother claimed to have seen. 2Greenbrier Independent Feb 25, 1897

Shadows in His Past

As the investigation deepened, whispers about Trout Shue’s past began to spread through Greenbrier County. Locals had questions. Who was this man Zona had married? Where had he come from? And what had he left behind? It turned out Shue had been married before….twice.

His first wife divorced him citing abuse. According to later reports, she said he had been violent and unpredictable. After the divorce, he left the area and eventually resurfaced in Pocahontas County, where he married again. His second wife died under strange circumstances, however I couldn’t find any mention of her death in the newspaper archives. Some claimed she had fallen and broken her neck. Others said she was struck by a falling object. Specifically, it is said she was helping Trout who was repairing a chimney when he dropped a brick onto her head “accidentally.” However, this didn’t show up in print until November 1977 Beckley Post-Herald article.

A Pattern Begins to Emerge

The details were vague, and no charges were ever filed, but the death had left behind a sense of unease. Neighbors began to wonder if Zona had truly been his first victim, or just the first one anyone had dared to investigate.

The Staunton Spectator, writing in April 1897, was blunt:

“It may be noted that this was his fourth wife and he is only about 30 years of age. He was also found to have secured the promise of another woman to marry him.”

The timeline was compressed. Shue had divorced one woman, buried another, and married Zona all within a span of a few short years. The newspapers noted that he had already secured a promise of marriage from yet another woman, even while awaiting trial. People felt most disturbed by a statement Shue repeated more than once: he planned to have seven wives. He may have said it as a joke, but no one was laughing. Zona had been number three.

This wasn’t just gossip. In a letter written in 1903, Judge J.M. McWhorter, who presided over the trial, confirmed that Zona was indeed Shue’s third wife, and that he had boasted of his desire to have seven. Although the Beckley Post-Herald didn’t publish McWhorter’s account until decades later, it remains the most concrete and credible source for both Shue’s marital history and the unsettling remark he made about wanting seven wives.3Beckley Post-Herald Dec 18, 1958

After the arrest, his past caught up with him. Courtrooms began airing what had once been Shue’s private history, and newspapers from Greenbrier to Richmond printed every detail. He had not just lost control of the story. He had become the story.

Testimony from the Grave

The trial of Erasmus “Trout” Shue began in June 1897, at the Greenbrier County Courthouse in Lewisburg, West Virginia. The prosecution presented a case built on medical evidence and circumstantial details. Doctors discovered a broken neck, a crushed windpipe, and deep bruising across Zona’s throat and chest. They made it clear: she hadn’t fallen, and she wasn’t sick.

Witnesses testified that Shue had dressed Zona’s body himself, refusing to let anyone else touch her and tying a high collar and veil tightly around her neck, even though it was uncustomary. When the coffin was open, he stayed close to her head. When it was closed, he wept loudly. But few believed the grief was genuine.

Still, it was the testimony of Mary Jane Heaster that seized the courtroom’s attention. She took the stand calmly, wearing a simple black dress. The defense expected a broken, grieving mother. What they got was a woman with clarity and conviction.

Mary Jane Takes the Stand

The defense attorney began cautiously:

Q: I have heard that you had some dream or vision which led to this postmortem examination?

A: They saw enough theirselves without me telling them. It was no dream. She came back and told me.

Mary Jane explained that over four nights, her daughter had appeared to her. Each time, she gave more detail. Zona had told her that Shue came home angry because there was no meat prepared for dinner. She said she had listed the food on the table: butter, apple-butter, preserves, and several jellies. But it wasn’t enough for him. He became furious.

“He just flew into a rage,” Mary Jane said, quoting her daughter. “He grabbed me on each side of my head and twisted it until my neck was broken, at the first joint.”

The courtroom was absolutely hanging on every word that Mary Jane said. Zona described the house to her in detail, even pointing out a spot behind a loose plank in the cellar where something was hidden. Mary Jane had never been there, but when she described it later to neighbors, they said the description matched exactly.

Q: Now, Mrs Heaster, don’t you know that these visions…were nothing more or less than dreams, founded upon your distressed condition of mind?

A: No sir, I don’t. The Lord sent her to me to tell it.

She adamantly insisted she was wide awake each time. That she touched her daughter, and one of my favorite parts of the testimony that she “tried to feel the coffin, but there was none.” Mary Jane was curious to know if ghosts floated around in their coffins apparently. I think it’s just a really cool insight from that time period. She went on to say that Zona stood as real and solid as any person in the room. When she left, Mary Jane said, she turned her head completely around, “like she wanted me to remember.” Just imagine how freaky that must’ve been for Mary Jane.

Q: Did she say anything else to you?

A: Yes, she told me she had done all she could. I believe she did.

Q: Did you tell anyone else?

A: Yes, my neighbors. And when they saw her, she was exactly as I said she’d be.

The defense pushed her to admit these were grief-fueld dreams, but Mary Jane stood firm.

Q: Then you insist that she actually appeared in flesh and blood to you upon four different occasions?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Are you not considerably superstitious?

A: No, sir, I am not. I never was before, and I am not now.

Q: Do you believe the scriptures?

A: Yes, sir, I do. Don’t you?

Q: Would you be willing to say under oath that you saw your daughter’s spirit and that she told you how she died?

A: I have said it already. And I’ll say it again.

The defense eventually backed down.

The Ghost in the Courtroom

While the judge reminded the jury that they were to weigh all testimony carefully, he did not strike Mary Jane’s account from the record. In the end, it was the medical evidence that carried the case, but her testimony stayed with them. Whether they believed in ghosts or not, Mary Jane had told the same story from the start. The postmortem examination later confirmed everything her daughter had revealed to her, the broken neck, the place of death, and the violent cause.

Zona Heaster may have died in January, but in June she still had the final word.

The Defense Responds

After Mary Jane Heaster stepped down, the courtroom shifted. The prosecution had made its case: a body with signs of violence, a husband with something to hide, and a mother whose visions matched the injuries revealed by the autopsy. Now, it was Shue’s turn to speak.

Trout took the stand in his own defense. I imagine he must’ve been quite sure of himself and his testimony. He testified for an entire afternoon. His lawyers did little to restrain him. The court gave him too much space, and he filled it with odd details. He spoke at length, offering painstaking descriptions of irrelevant incidents, avoiding the heart of the matter. He claimed he loved Zona dearly. He swore he was innocent, called God as his witness, and told the jury to “look into [his] face” and decide if a guilty man sat before them.

He acknowledged that he had served time in the penitentiary for horse theft in Pocahontas County but didn’t elaborate. He dismissed the case against him as “spite work,” claiming the townspeople had never liked him. He denied nearly everything other witnesses had said. But it wasn’t really what he said, it was how he said it.

Shue’s performance on the stand left many uneasy. The Greenbrier Independent noted that his testimony, manner, and tone made a distinctly unfavorable impression on the courtroom. His long-winded answers, his refusal to confront the specifics of Zona’s death, and his melodramatic appeals to emotion rang hollow. Whatever sympathy he had once commanded was long gone.

The Verdict

Once testimony concluded, Judge J.M. McWhorter gave the jury their instructions. They were to weigh the case based on the evidence: medical findings, witness accounts, and the conduct of the accused. There was no eyewitness to the crime, and the prosecution had no physical proof of guilt beyond the autopsy. The strength of the case rested almost entirely on circumstantial evidence, supported by the consistent pattern of Shue’s behavior, both before and after Zona’s death.

After a seven day trial and deliberations that took at most a couple of hours, the jury returned a verdict: Guilty of murder in the first degree. The sentence was life imprisonment at the state penitentiary in Moundsviille.

A Rope in the Shadows

Not everyone was satisified with the outcome. Some believed the death penalty should have been imposed. In the days following his conviction, rumors of a lynching began to spread through the Meadow Bluff district. On Sunday, July 11, a group of men planned to gather at the old campground eight miles west of Lewisburg. Their aim was clear: to storm the jail and hang Shue.

Word of the plan reached George M. Harrah, a local resident. He rode hard to Sheriff Hill Nickell, who then traveled with Harrah toward Lewisburg. As they passed the campground around nine o’clock that night, they saw several men already assembled in the shadows. Shortly after, they were stopped by four armed members of the mob. The sheriff nearly drew his pistol but recognized one of the men and instead chose to talk. He and Harrah were escorted to a nearby home, where Nickell managed to convince the group to disband.

What the mob didn’t know was that Shue had already been moved. A fishing party had caught wind of the planned lynching and tipped of Deputy John Dwyer, who quietly took Shue to a hiding place in the woods outside town. Shue would be transferred to Moundsville a few days later.

The court ordered Shue’s ring and penknife, taken from Zona after her death, to be returned to her father. The gesture was small and final. The case had ended, but the story was far from over.

Legacy of the Greenbrier Ghost

The story of Zona Heaster Shue did not end with Trout’s conviction. It lived on in courthouse transcripts, newspaper columns, family stories, and Appalachian folklore. But unlike most ghost tales, this one also left behind a verdict. A jury found a man guilty of murder, and a mother’s unshakable belief in her daughter’s spirit played a role in that outcome.

It’s often called the only U.S. case where a ghost’s testimony helped convict a killer. That may be an oversimplification, but it isn’t wrong. Mary Jane Heaster’s account moved a prosecutor to act. Her insistence on the truth forced a second look at a death that might otherwise have faded into quiet tragedy.

Zona’s grave still stands in Greenbrier County. Nearby, a state historical marker tells the story of the Greenbrier Ghost, condensed into a few short lines. But the full truth is more complicated, more human, and more haunting. It’s the story of a woman who died under suspicious circumstances. Of a mother who wouldn’t let her memory be buried. And of a justice system that listened to the voice of a grieving heart and the ghost it claimed to hear.

Know a story as strange as Zona’s?

Tell us in the comments, or reach out if there’s a haunting or legend you’d like to see explored on The Dead History. The next post might just be yours.

Sources:

- Greenbrier Independent, October 22, 1896 – Marriage announcement of E.S. Shue and E.J. Heaster

- Greenbrier Independent, January 28, 1897 – Initial death notice for Zona Shue

- Greenbrier Independent, February 25, 1897 – “Foul Play Suspected” article reporting on exhumation and postmortem

- Greenbrier Independent, June 24, 1897 – Trial begins, jury selected

- Greenbrier Independent, July 1, 1897 – Full trial coverage including Mary Jane Heaster’s testimony and verdict

- Greenbrier Independent, July 15, 1897 – Account of attempted lynching and Shue’s transfer to Moundsville

- Staunton Spectator, April 8 and July 8, 1897 – Background on Shue’s criminal record and prior marriages

- Richmond Dispatch, March 2, 1897 – Coverage of the postmortem and charges filed

- The Independent-Herald, February 18, 1904 – Retrospective analysis of Mary Jane Heaster’s account

- Beckley Post-Herald, March 5, 1953 – Retelling of the case and ghost testimony

- Beckley Post-Herald, December 18, 1958 – Publication of Judge J.M. McWhorter’s letter describing trial outcome

- Beckley Post-Herald, November 12, 1977 – Folkloric retelling including reports of Shue’s prior wives and behavior

- West Virginia State Archives – Birth registry showing Zona Heaster’s son born November 29, 1895

- West Virginia Vital Records – Death registry entry for Zona Heaster Shue

- Oral histories compiled by Greenbrier County residents and descendants

Hello. I knew the story of Zona Shue and more than just a ghost story, it is about the courage and conviction of a mother to face a court and social judgment to seek justice for her daughter and get justice done. If it is still difficult today, what can I say about it back then? But you brought up many details that I was unaware of. Your research is exquisite, you delve into the themes and your narrative captivates the reader. I loved finding your blog.

Feedback

Hi Lisi, thank you so much for this thoughtful comment. You said it perfectly: beneath the ghost story is a mother who refused to stay quiet, even when everything was stacked against her. I’m really glad the deeper context came through for you, and it means a lot to hear that the research resonated. I’m so happy you found the blog, welcome to this little corner of haunted history!