Some outlaws are remembered for their daring heists or legendary shootouts. Elmer McCurdy is remembered for something far bizarre. Spending more than six decades as a carnival attraction after his death, traveling the country as a mummified curiosity before anyone realized the “wax dummy” hanging in a California funhouse was actually a real human corpse.

This is the story of America’s most well-traveled dead man and the bizarre chain of events that turned a failed bank robber into one of history’s most macabre tourist attractions.

A Troubled Beginning

Elmer J. McCurdy entered the world on New Year’s Day 1880 in Washington, Maine, already carrying the weight of scandal. Born to unmarried 17-year-old Sadie McCurdy, he was quickly adopted by his aunt and uncle to spare his young mother the social stigma of raising an illegitimate child. This family secret would remain hidden until he was ten years old.

When his adoptive father George died of tuberculosis in 1890, Sadie finally revealed the truth about Elmer’s parentage. The revelation seems to have caused something to break inside him. Family accounts describe how he became “unruly and rebellious,” turning to alcohol as his constant companion. What began as teenage defiance would evolve into a lifelong battle with alcoholism that would sabotage every opportunity that came his way.

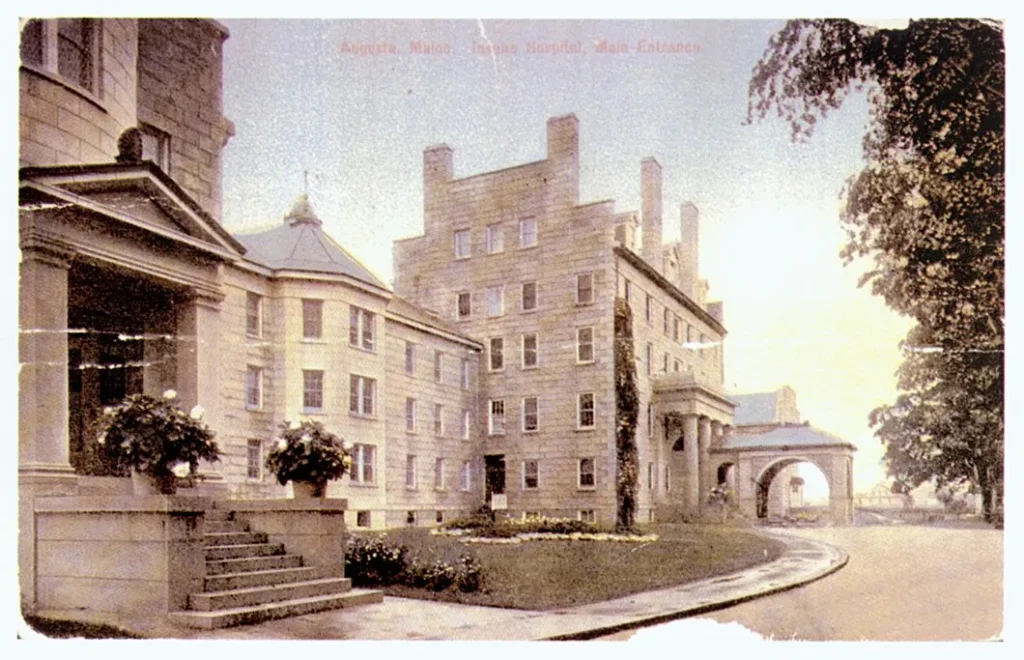

McCurdy eventually learned the plumbing trade, but his drinking made him unreliable. Jobs came and went, including working as a painter at the Maine Insane Hospital. Then, in 1900, tragedy struck twice, both his mother and grandfather died within two months of each other. His mother’s death certificate coldly lists the cause as peritonitis, but for Elmer, it meant the severing of his last family ties. With nothing left to anchor him to Maine, he drifted westward, moving from town to town as a plumber and miner, always one drink away from losing whatever work he’d found.

An Explosive Education

In 1907, perhaps seeking structure or simply a steady paycheck, McCurdy enlisted in the U.S. Army. At the time of enlistment, the Army listed Elmer’s occupation as miner. Fort Leavenworth became his temporary home, where he received training that would later define his criminal career in the most literal sense. He learned to handle nitroglycerin for demolition work and operated machine guns. After three years of military service, he received an honorable discharge from the Quartermaster Corps on November 7, 1910.

Little did the Army know they had just trained one of America’s most incompetent bank robbers.

The Yeggman Method of Safecracking

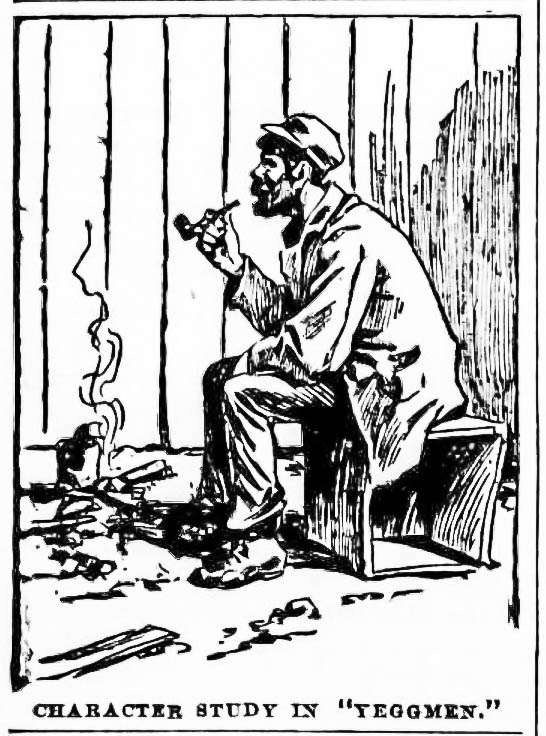

This military training, especially in nitroglycerin handling, proved crucial. At the time, criminals known as yeggmen roamed the country, specializing in explosive safecracking. The yeggman method involved extracting nitroglycerin from dynamite in makeshift camps along railroad tracks, then storing the volatile liquid in rubber containers or hot water bottles. When preparing for a robbery, yeggmen would use soap to fashion a channel or “cup” around a safe’s door, pour in the nitroglycerin, and ignite it to blast the safe open. This technique was notoriously risky, often resulting in the destruction of both the safe and its contents if too much explosive was used.

Yeggmen were infamous for their itinerant lifestyles, frequently traveling via freight trains and targeting rural banks, post offices, and payroll safes. Law enforcement at the time, including Pinkerton detectives, specifically classified these explosive-wielding criminals as yeggmen, a term that surged in popularity during McCurdy’s era. McCurdy’s approach mirrored these methods: his botched 1911 train robbery in Oklahoma saw him use so much nitroglycerin that he destroyed the safe’s contents rather than securing the loot, a hallmark of inexperienced or unlucky yeggman.

Elmer’s shift from Army engineer to outlaw reflected a familiar pattern of the era. Men trained in technical trades or military service often found those same skills useful in less lawful work. Among the early twentieth-century yeggmen, precision and calculation were as valuable as nerve.

The Most Bungled Heists in History

McCurdy’s criminal career lasted less than a year, but in that time, he managed to establish himself as perhaps the worst train and bank robber in American history. Quite an accomplishment I would say! Armed with military demolition training and crippled by alcoholism, he embarked on a series of heists that read more like dark comedy than serious crime.

His first major robbery in March 1911 targeted a Missouri Pacific train. McCurdy’s plan was simple: use nitroglycerin to blow open the safe and make off with the cash. The execution was catastrophic. He used far too much explosive, creating a blast so powerful it didn’t just open the safe, it melted the silver coins inside, fusing them permanently to the safe’s interior walls. The gang’s take from this destruction? A measly $100 (equivalent of about $3400 today.) The federal government, however, was not amused, placing a $2,000 ($68k today) bounty on McCurdy and his accomplice Walter Jarrett.

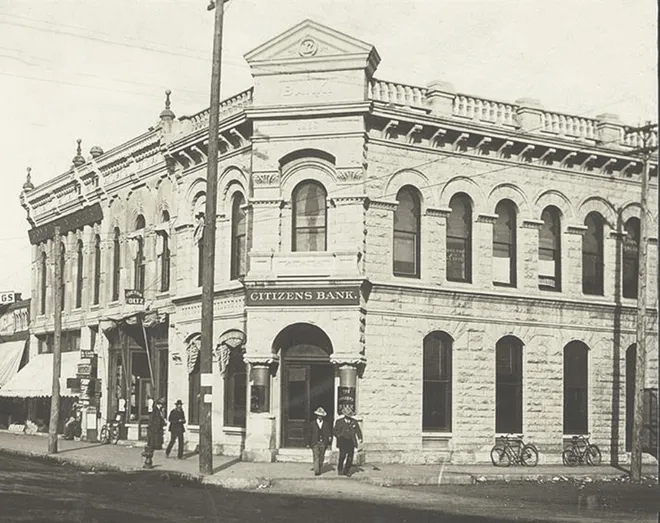

Undeterred by this spectacular failure, McCurdy tried again in September 1911 at The Citizens Bank in Chautauqua, Kansas. After spending two hours painstakingly breaking through the bank’s wall, he set another nitroglycerin charge. This time, the explosion was so violent it launched the entire vault door out of the building and into the street. The safe inside? Completely undamaged. The gang fled with approximately $150 in loose coins.

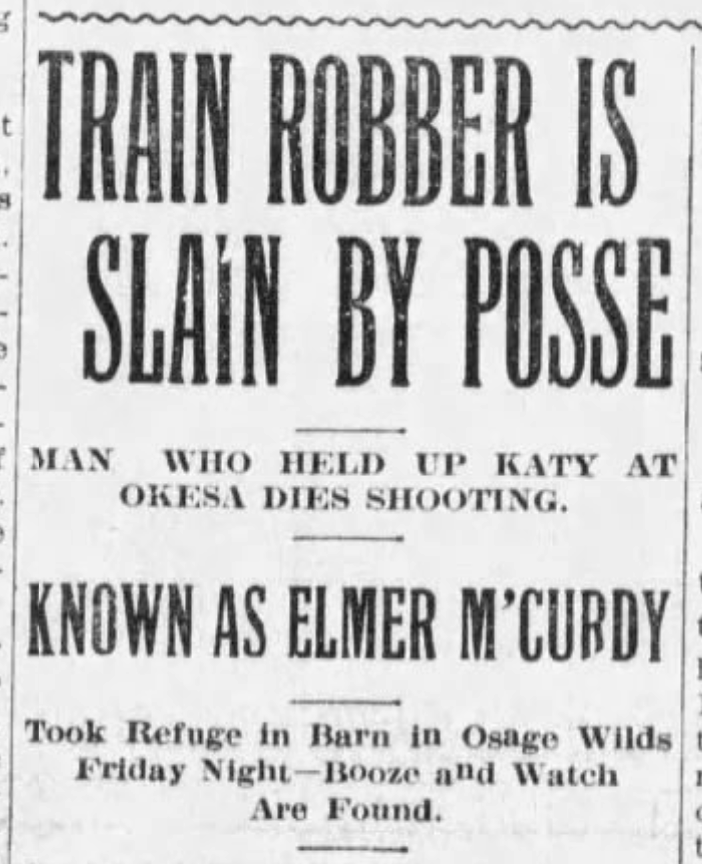

But McCurdy’s masterpiece of criminal incompetence came on October 4, 1911, near Okesa, Oklahoma. He and his gang had received intelligence about a Katy Train carrying a $400,000 royalty payment destined for the Osage Nation. This would be a score that would set them up for life. Instead, they stopped the wrong train entirely, robbing a regular passenger service. Their haul from this “one of the smallest in the history of train robbery” consisted of $46, two jugs of whiskey, a revolver, a coat, and the conductor’s watch.

Death Comes Calling

Disappointed and likely drunk, McCurdy retreated to a friend’s ranch near Bartlesville, Oklahoma. By this time, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and trichinosis were ravaging his body. The $2,000 bounty on his head made him a marked man, but McCurdy seemed more interested in drowning his sorrows than evading capture.

On the morning of October 7, 1911, three deputy sheriffs tracked him to a hay shed on the property. What followed was an hour-long shootout that ended with a single bullet to McCurdy’s chest. The notoriously bad outlaw who had terrorized trains and banks across the Midwest was dead at just 31 years old.

But for Elmer McCurdy, death was just the beginning of his strangest adventure.

The Birth of a Sideshow Star

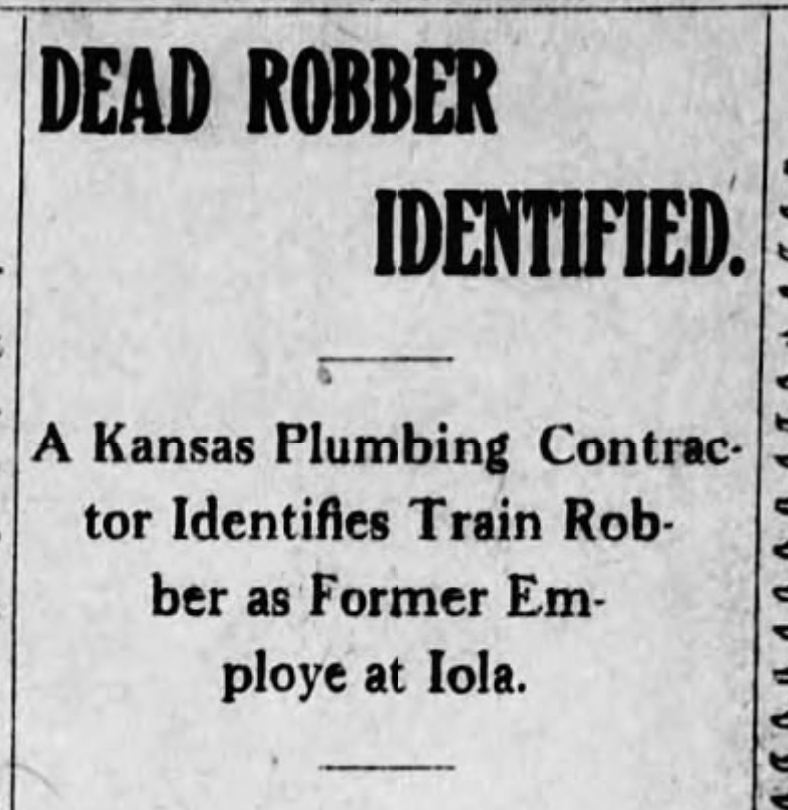

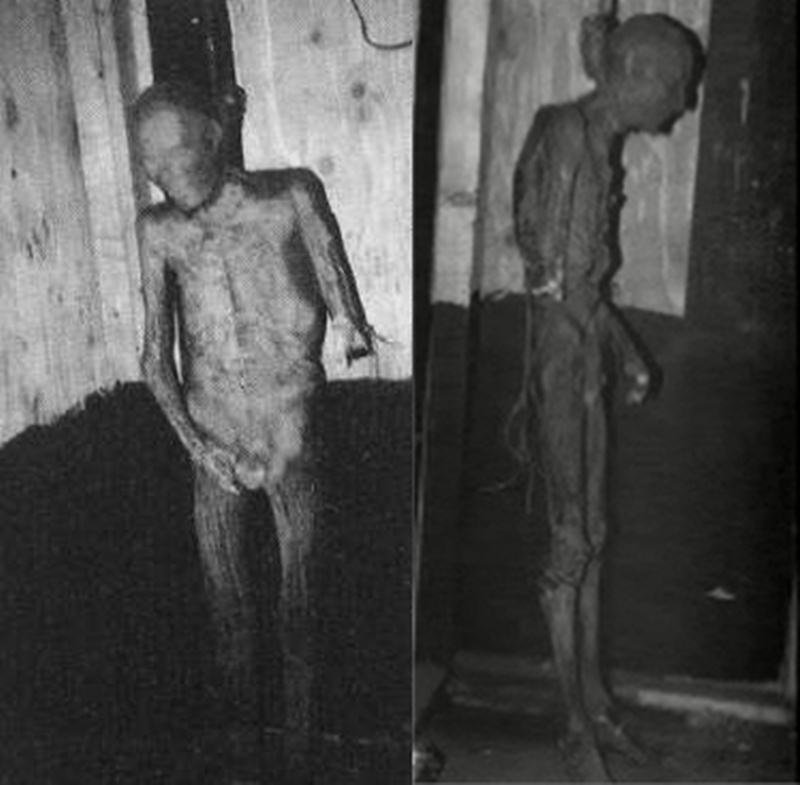

Authorities delivered McCurdy’s unclaimed corpse to undertaker Joseph L. Johnson in Pawhuska, Oklahoma. Using an arsenic-based preservative which was standard for the era, Johnson embalmed the body and waited for someone to claim it. Days turned to weeks, then months. No family came forward, and Johnson’s fees remained unpaid.

Faced with a perfectly preserved corpse and mounting storage costs, Johnson made a decision that would launch McCurdy’s second career. He propped the body up in a corner of his funeral home, rifle in hand, and began charging visitors a nickel to see “The Bandit Who Wouldn’t Give Up” or “The Embalmed Bandit.”

The attraction was an immediate hit. For five years, locals and travelers alike lined up to gawk at the preserved outlaw. McCurdy had found more success in death than he ever had in life.

The Great Deception

In October 1916, two well-dressed men arrived at Johnson’s funeral home claiming to be McCurdy’s long-lost brothers from California. They had come, they said, to finally give poor Elmer a proper burial. Johnson, perhaps relieved to finally be rid of his profitable but macabre houseguest, released the body to these supposed relatives.

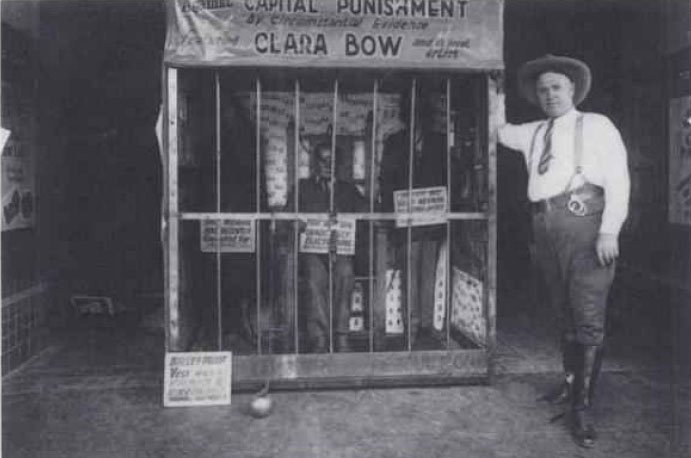

The men were actually James and Charles Patterson, owners of the Great Patterson Carnival Shows. Within days, McCurdy was back on display, now traveling the country as “The Outlaw Who Would Never Be Captured Alive.” What followed was a six-decade odyssey that would take the preserved outlaw from coast to coast and beyond.

A Star is Born (Again and Again)

McCurdy’s posthumous career was remarkably diverse. In 1922, he joined Louis Sonney’s traveling “Museum of Crime,” where he shared billing with other macabre curiosities. The 1930s saw him move into Hollywood, where exploitation film director Dwain Esper used the corpse in theater lobbies to promote his 1933 film Narcotic!, billing McCurdy as a “dead dope fiend”, a considerable career pivot for a former train robber.

He even had a brief movie career, appearing in the 1967 film She Freak. (Side note: I watched She Freak a couple of times and couldn’t spot Elmer. Let me know if you spot him!) Through sales and resales, McCurdy’s mummified remains eventually found their way to The Pike, an amusement park in Long Beach, California. By 1976, he was hanging from a gallows in the “Laff in the Dark” funhouse, covered in garish DayGlo orange-red paint, mistaken by visitors and employees alike for just another wax dummy in a house of manufactured horrors.

The Shocking Discovery

On December 8, 1976, a television production crew filming The Six Million Dollar Man at The Pike needed to move what they assumed was a hanging mannequin. When a prop man grabbed the figure’s arm, it broke off, revealing not wax or plastic, but genuine human bone and muscle tissue.

The Los Angeles coroner’s office confirmed the shocking truth. This wasn’t a prop, but an actual human corpse. The investigation that followed read like a detective story. The body had been preserved with arsenic-based embalming fluid. A gas check from a bullet first manufactured in 1905 was lodged in the chest. Most tellingly, inside the corpse’s mouth were a 1924 penny and ticket stubs from Louis Sonney’s Museum of Crime.

These clues led investigators to Dan Sonney, son of the museum’s owner, who suggested the mummy might be Elmer McCurdy. Meanwhile, amateur historians in Guthrie, Oklahoma, had reached the same conclusion. Forensic anthropologist Dr. Clyde Snow made the positive identification by superimposing X-rays of the skull over photographs taken of McCurdy after his death in 1911.

Finally at Rest

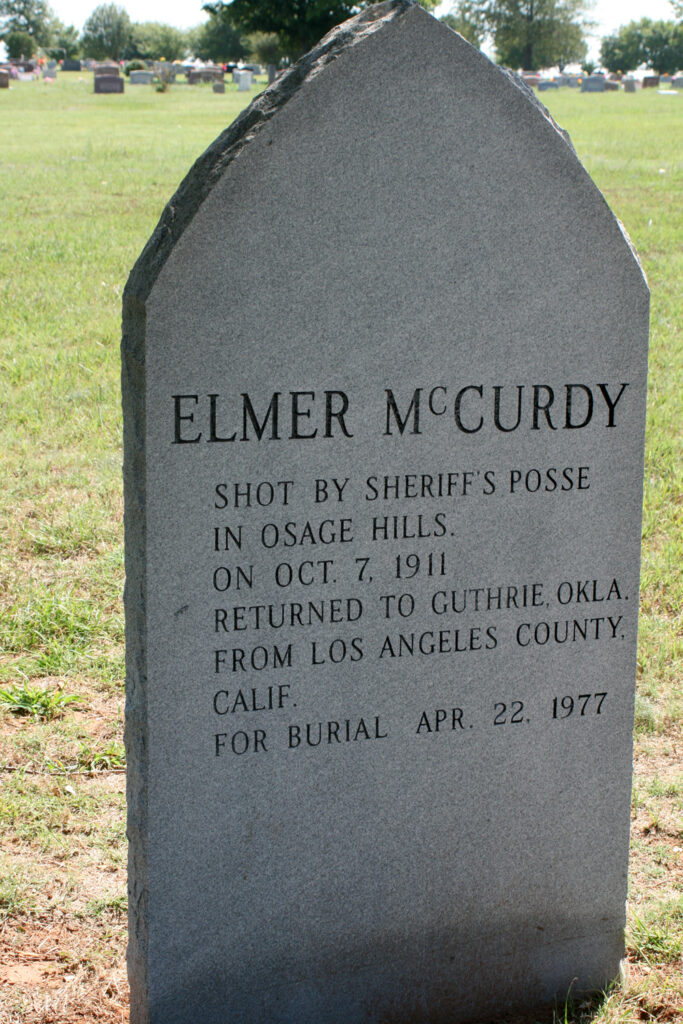

After spending 66 years traveling the country as a curiosity, Elmer McCurdy was finally on his way home. On April 22, 1977, his remains were transported to Guthrie, Oklahoma, and laid to rest in the Boot Hill section of Summit View Cemetery, next to fellow outlaw Bill Doolin.

Cemetery officials, perhaps mindful of McCurdy’s tendency to wander, took no chances. They poured two feet of concrete over his casket, ensuring that this time, the outlaw who wouldn’t give up would finally stay put.

McCurdy’s bizarre story captured the American imagination, eventually inspiring the Broadway musical Dead Outlaw in 2025. This is a uniquely American tale that combines elements of crime, carnival history, and a reflection on death and dignity in the era of mass entertainment.

In the end, Elmer McCurdy achieved in death what had eluded him in life: he became unforgettable. Though not quite in the way he might have hoped.