A Mysterious House in the Water A couple of years ago, I was driving from Ogden to the small

A Long-Awaited Visit to Pennhurst Like the Goldfield Hotel, Pennhurst State School and Asylum was on my Top 5

The Legend: A mother took her two young children for a drive, believing they were possessed by the devil.

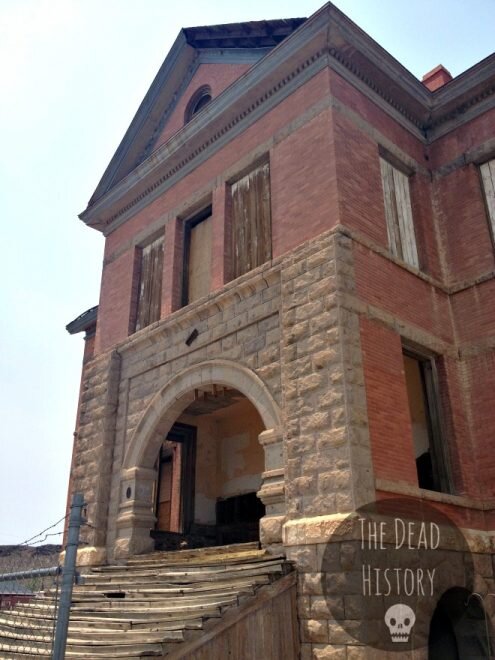

A School Frozen in Time On the corner of Euclid & Ramsey in Goldfield, Nevada, the Goldfield High School

For decades, the Brigham City Indian School sat abandoned, its empty halls fueling eerie stories of restless spirits and