The Legend of the Weeping Woman of Logan Cemetery:

If you stand in front of the Weeping Woman of Logan Cemetery at midnight under a full moon and say, “Weep, woman, weep,” the statue will cry. At least, that’s what the legend claims.

Some say she mourns the loss of her children; only three of her eight lived to adulthood. Depending on who you ask, she either weeps only under the full moon or on the anniversary of each child’s death. Over the years, visitors have sworn they’ve seen streaks on her face, as if the stone itself holds onto her sorrow.

The Tragic History Behind the Weeping Woman:

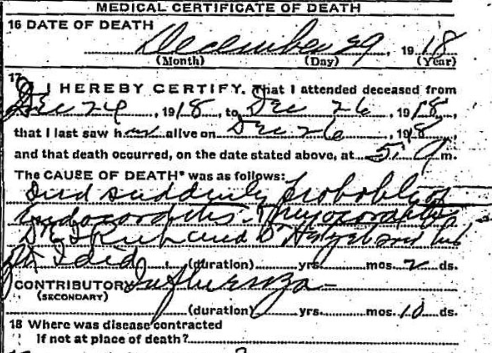

Olif Cronquist built this monument in memory of his wife, Julia, who died on January 8, 1914, from valvular heart disease, likely a lasting complication of scarlet fever. As one of Cache County’s first commissioners and a well-known dairy farmer, Olif left his mark on the community, but his legacy remains forever tied to the heartbreak that shaped his family’s history.

Julia and Olif’s first child, Margaret, was born in 1880, followed by twin boys, Olif and Oliver, in 1883. Their son Orson arrived in 1888, and for a time, life seemed full of promise. Then, in March 1889, scarlet fever swept through their home. Within days, the twins were gone, taken by the disease before their sixth birthday. Julia survived the illness, but it left her with lasting heart damage—an invisible scar that would follow her for the rest of her life.

With the birth of their son Elam in 1891, it seemed as though the worst had passed for the Cronquist family. In 1894, Julia gave birth to another daughter, Lilean, but records are unclear—she may have been stillborn or lived only a short time. In just five years, they had buried three of their six children.

Despite their losses, life carried on. Julia and Olif welcomed another daughter, Emelia, in 1896, followed by Inez in 1899. But their happiness didn’t last long. By late February 1901, scarlet fever had returned, and this time, it took Emelia, age four, and Inez, just two years old. The sisters were buried together in a specially built casket.

Twelve years earlier, Julia and Olif had stood in this same cemetery, mourning the deaths of their twin boys, Olif and Oliver. Now, they found themselves in the same place, saying goodbye to their daughters—history, in the cruelest way, repeating itself.

A Final Farewell

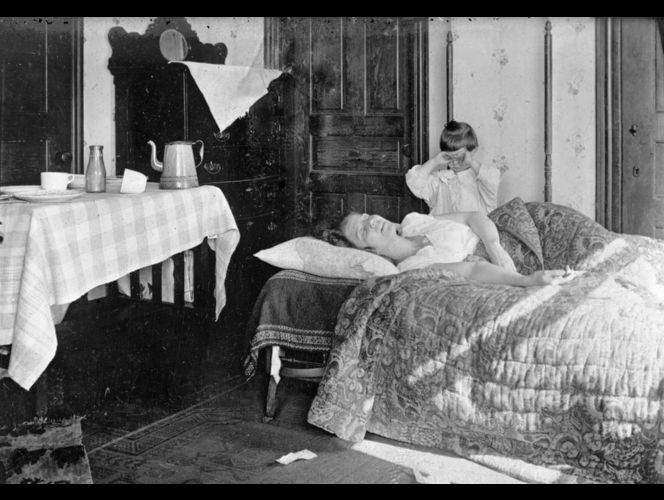

Mourners at the funeral watched in sorrow as pallbearers placed the small casket over the grave. When they removed the lid for one final viewing, the girls lay side by side, their bodies gently positioned as if they were still whispering secrets to one another—only now, death had silenced their conversation. Those who attended later described the scene as both beautiful and devastating: the two girls, fair as angels, half-facing each other, cold in death’s embrace.

Julia was inconsolable. Witnesses feared she might not survive the weight of her grief. She had already buried four of her children, and now she was saying goodbye to two more. Even the strongest hearts at the service were moved to tears as she stood over the casket, visibly shattered.

Even in life, Julia’s sorrow was impossible to ignore. Passersby often saw her at the cemetery, kneeling by the graves of her children, lost in grief. Some say she never truly left. Maybe that’s why the legend lingers—because some grief is too heavy to fade, even in death.

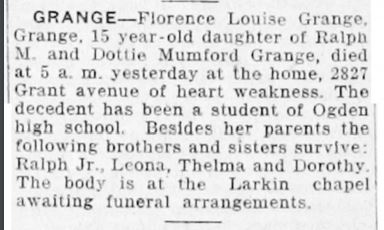

By the time Julia turned 40, she had buried five of her eight children. Loss had become a familiar presence in her life, but it never grew easier. Family history remembers Julia as inconsolable, often seen kneeling at their graves, lost in grief. Over time, her health declined, weakened by the long-term effects of scarlet fever. She passed away at 3 a.m. on January 14, 1914.

Her obituary described her as “a splendid type of woman, tender, loving, patient, and true, bearing her great burden without complaint and always seeking the happiness and comfort of those about her.”

How to Visit the Weeping Woman of Logan Cemetery

Olif commissioned the monument in 1917, a lasting tribute to his wife and the children they lost. Today, the Weeping Woman watches over the Cronquist family plot in Logan City Cemetery. If you want to see her for yourself, you’ll find her at 1000 N 1200 East in Logan, on the campus of Utah State University. The family’s plot is located at A_ 100_ 45_ 4.