A Valentine’s Day Visit to the Mausoleum I drive past the Mount Ogden Mausoleum almost daily and have always

The Legend: A mother took her two young children for a drive, believing they were possessed by the devil.

Tucked away in Spanish Fork Canyon, Mill Fork Cemetery is easy to miss — but once you spot it,

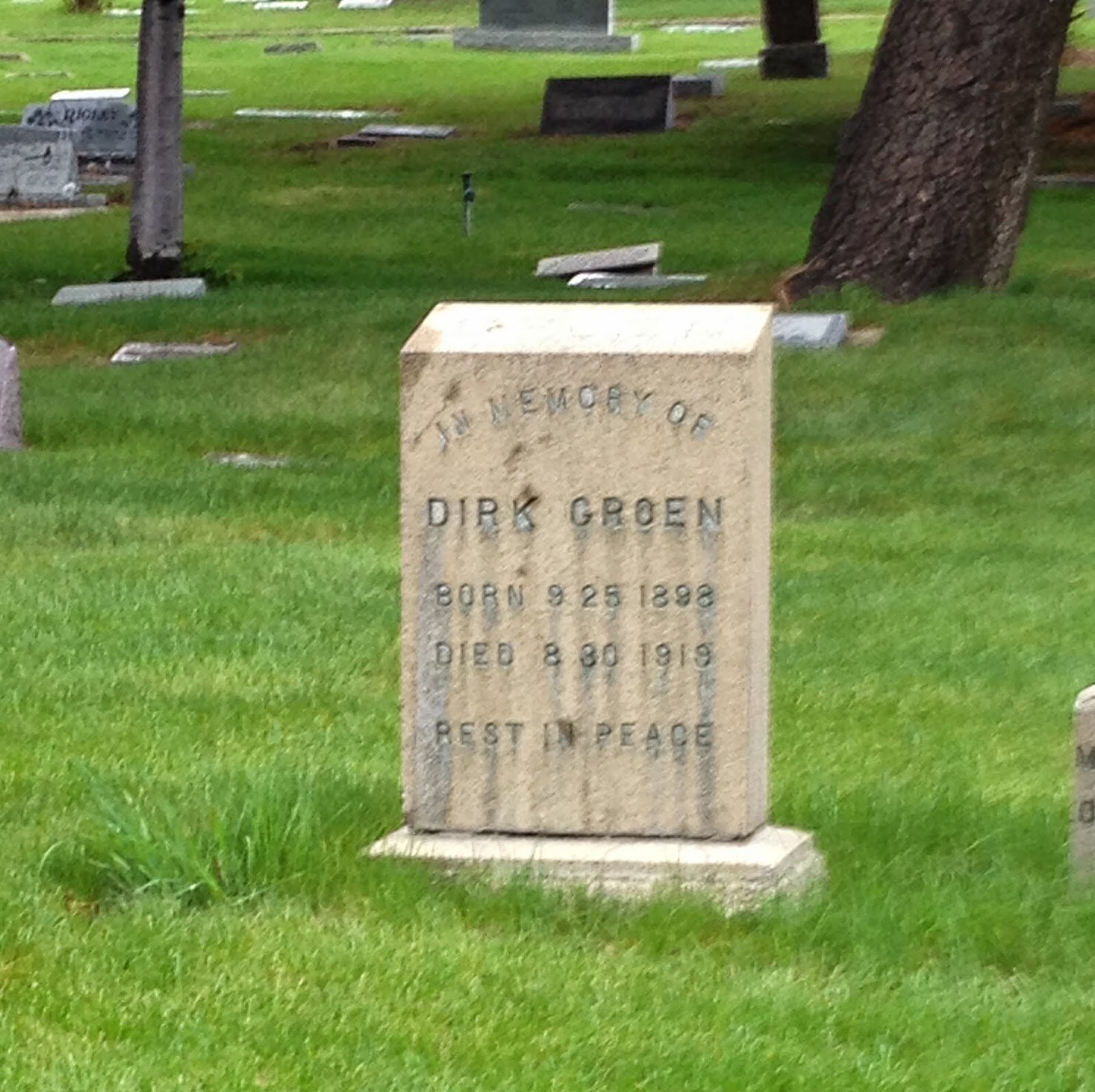

A Headstone That Caught My Eye Dirk Groen’s grave in Ogden Cemetery caught my eye one day as I

Discovering a Unique Monument Much to my children’s disappointment, I love wandering through cemeteries, camera in hand. They usually

The Legend: If you visit Emo’s Grave, circle the Moritz Columbarium three times while chanting "Emo, Emo, Emo" and

For decades, the Brigham City Indian School sat abandoned, its empty halls fueling eerie stories of restless spirits and

The Legend of Jean Baptiste Salt Lake City is home to one of the strangest true-ish legends that I’ve

The Legend of the Weeping Woman of Logan Cemetery: If you stand in front of the Weeping Woman of

According to local legend, if you flash the lights of your car onto Flo’s grave three times, her ghost