On quiet nights along the shore of Stony Creek, a voice rises from the darkness. The wind carries a question, soft but insistent. Where is my head? Who’s got my head? The Stony Creek headless ghost has haunted these waters for generations. Some know the story well. Others only hear whispers. A headless figure, staggering through the woods, searching for something lost.

urban legend

The Witch of Parley’s Hollow

Urban legends often revolve around harmless dares and thrill-seeking rituals. But sometimes, these stories take a darker turn—turning real people into targets of fear and speculation. Such was the case with the so-called Witch of Parley’s Hollow, a woman known as Crazy Mary or Bloody Mary. From the 1930s to the 1950s, parents warned children to stay away from Crazy Mary’s house.

So it naturally turned into a challenge to see if they could spot the Witch of Parley’s Hollow. She was a recluse, and from the stories I found she had very eccentric behavior. One lady told a story of going to her house at midnight and watching her wildly playing her piano. The legend’s goal seemed simple: to spot her. Since people knew little about her, they spread rumors and branded her as crazy or even a witch. So who was Crazy Mary? And how did this legend surrounding her grow?

Dudler’s Inn

In 1864 the Dudler family built their homestead where Parley’s Historic Nature Park stands today. The family included Joseph Dudler, his wife Elizabeth (who went by her middle name, Susan), and his 7 children. Joseph was a carpenter by trade with a talent for brewing beer. He built a two-story home with a stone foundation and framed upper floor. By 1870 Joseph had extended the house into the hillside behind it, which included a brewery. The lower floor contained a stone “wine cellar” that served to keep things cool. You can still see this cellar along with pieces of the original foundation today.

Mr. Dudler’s beer business quickly took off and by 1892 he owned one or two saloons in Salt Lake City as well as a The Philadelphia Brewery Saloon in Park City. Travelers passing through Parley’s Canyon stayed at the homestead, which also operated as an inn. By the early 1900s, it had become a saloon.

Death & The Dudler Family

Joseph Dudler died suddenly on the 21st of October, 1897. The responsibility of running the brewery and maintaining Dudler’s Inn fell on his wife and children. It seems they were a feisty bunch and were definitely up to the challenge. In 1898, the Salt Lake County Sheriff arrived at the property in the middle of the night to shut off access to a canal the Dudlers had built to supply their brewery with water. Mrs. Dudler was not having it and along with her sons and Loretta, kept the canal open and the Sheriff left embarrassed. The dispute escalated into a major legal battle when Salt Lake City sued Mrs. Dudler, claiming she had taken water she wasn’t entitled to use.

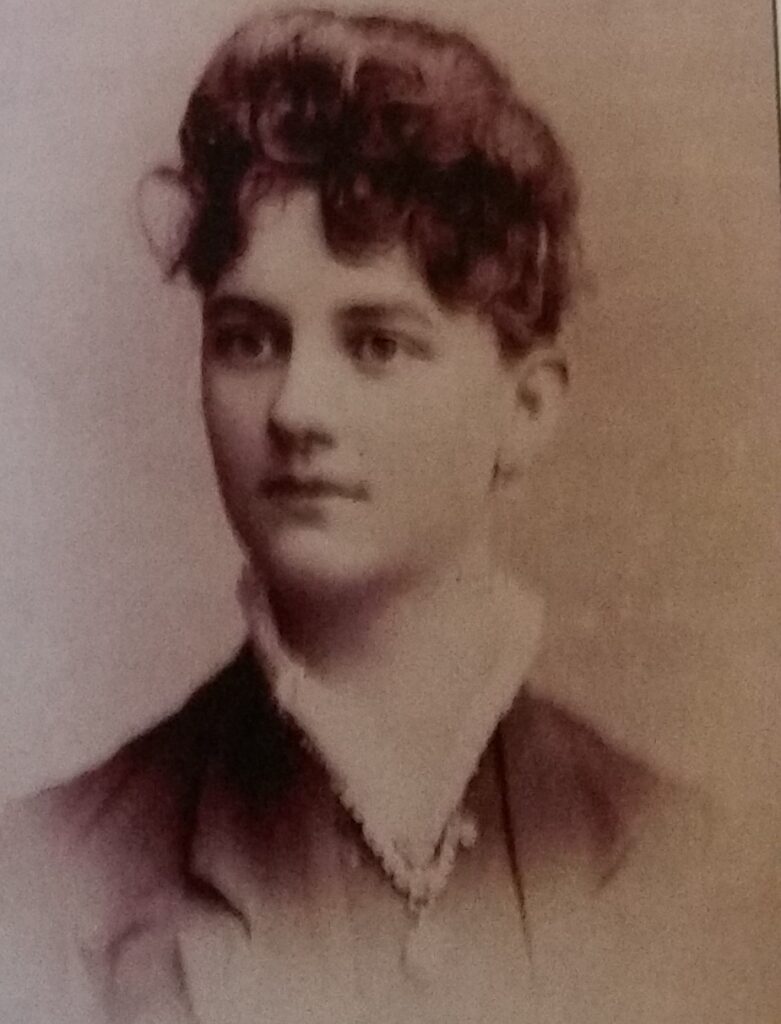

Mrs. Dudler repelled the suit successfully and was able to maintain her claim to water rights of the canal. Just a few years later on December 26th, 1904, Mrs. Dudler succumbed to pneumonia and died at the family homestead. Joseph and Susan Dudler had three daughters: Amelia, Louisa, and Loretta. Louisa was the only one who appears to have had a “normal” life. She married, left Parley’s Hollow, and started her own family

Troubled Lives and Tragic Fates

Amelia Dudler was a popular girl in her teenage years. She along with Loretta spent a lot of time in Park City, and both attended St. Mary’s Academy in Park City. Loretta mastered the piano and organ, earning awards for her musical talent and beautiful singing voice. Amelia Dudler married but eventually fell into addiction, relying on morphine and cocaine. She spent most of her adult life cycling in and out of jail and prison. Newspapers frequently reported on her, detailing her involvement in fights, arrests for drug use, and charges of disturbing the peace. In 1906 she was even a suspect in a murder case. She died on October 30th, 1907. The death certificate lists her death as natural, and specifically states she “was morphine and cocaine fiend.”

And then, there was Loretta. Loretta also called Retta or Mary moved back to the homestead after she finished school. Starting when she was 16 she began suffering from anxiety and severe depressive episodes. She met her husband, Harold Schaer while living in Park City, and they married in July 1907. Harold was a miner by trade, but after marrying Loretta he began work at the family brewery. In May 1908 their first child, Harold was born.

Life, at this point, seemed to be going pretty well for Loretta.A year later, Loretta lost another loved one, when her sister Louisa died at the age of 49. And three years after that, on July 26, 1912, her favorite brother Frank died from kidney disease. In a span of just a few years, she lost her mother and three siblings. Anyone would have struggled with this loss, but Loretta’s depression and anxiety made it even harder for her.

Loss and the Breaking Point

In March 1911 Loretta and Harold’s second son, Charles was born, but things were not going to stay relatively normal for Loretta for much longer. On October 18, 1912, Charles Schaer died at the age of 19 months from convulsions at the Dudler homestead. Loretta was devastated, and from all accounts, she was never the same after his death.

By 1930, Loretta’s husband had moved to Los Angeles, leaving her and their son, Harold Jr., behind in Parley’s Hollow. At 21, Harold Jr. inherited his mother’s musical talents and worked as a musician. In February 1933, he married and moved to California, where he spent many years as a studio musician for Paramount Pictures. Loretta was now living alone at Parley’s Hollow.

This is when the legend of The Witch of Parley’s Hollow got its start. Loretta didn’t leave the house much, and no one really came to visit her. By 1940, her house had fallen into severe disrepair, fueling the rumors that surrounded her. I’m sure many of the local people remembered the stories of her drug-addicted sister and the mother’s fight with the city over water. Many locals resented the Dudler family’s long-standing claim to the canal’s water, a conflict that had already painted them as outsiders. As the years passed, these lingering tensions helped fuel the legend of Loretta. Parents warned their children to stay away from her house, and soon, stories spread that the strange woman living there was a witch.

The Abandoned House

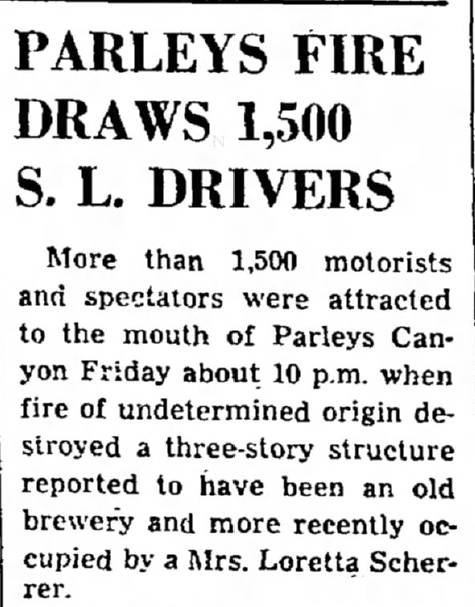

By the mid-1940’s Loretta was living in a nursing home near 2nd North and 5th West. Her house sat abandoned, and her son left all of the antique furniture, including Loretta’s beloved piano inside. On the evening of October 18th, 1952, the 40th anniversary of her son’s death, Loretta’s house went up in flames.The fire was determined to have been caused by vandals. In the years it sat empty the house of legend had turned into a party spot for local teens. The house wasn’t completely destroyed, but all of the antique furniture, including the piano was a loss. The house was now more derelict and creepy than ever.

Death of A Legend

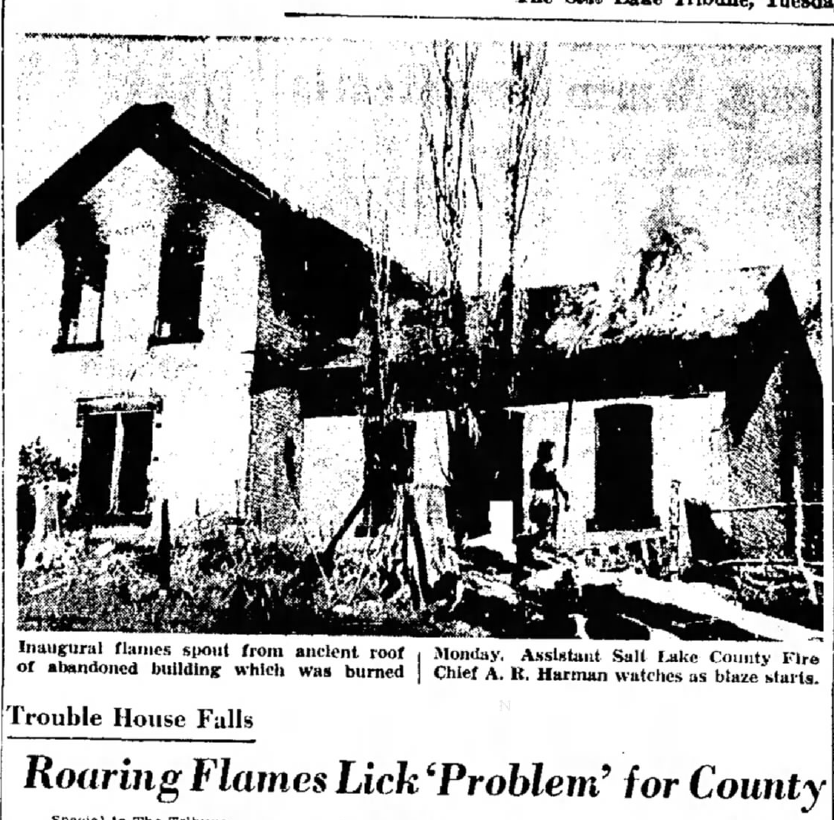

Early in the morning of March 22nd, 1959 an older woman who had lived a long yet difficult life died at the nursing home in which she had been living for years. Her siblings and estranged husband had all died before her, and her only living son lived in Las Vegas. Loretta Dudler Schaer lived to be 88 years old. Her obituary was very simple, and she is buried in an unmarked grave in the Salt Lake City Cemetery. Was she estranged from her son as well? It seems so but has been impossible to fully determine given what little information is available so far.In 1963, Salt Lake County set the Dudler house on fire and demolished it. They needed the land for the new freeway (I-80) that was going in.

If you ever visit Parley’s Historic Nature Park, take a moment to walk to the old Dudler wine cellar. Stand in the silence, where echoes of a long-forgotten legend linger, and pay your respects to a woman who was never a witch—only misunderstood.

What do World War I, anti-immigrant hysteria, and a vampire have in common? As strange as it sounds, they all converge in a forgotten cemetery in Park Hills, Missouri. This is where the legend of the Vampire of Gibson Cemetery comes to life.

Tucked away beneath layers of dead leaves and tangled brush, Gibson Cemetery barely looks like a cemetery anymore. Time and neglect have broken or scattered most of the headstones, wearing away the names.If you didn’t know better, you might not even realize you were standing among the dead.

And yet, there’s a story buried here—one that involves an accused vampire, an iron-barred grave, and a town gripped by fear.

A Cemetery Lost to Time

Gibson Cemetery dates back to the 1820s when the Gibson family first settled in the area. Originally a family burial ground, it eventually expanded to include others from nearby mining towns like Flat River, Rivermines, and Elvins. No one has determined the exact number of people buried here, but most graves date back to the early 1900s, when this part of Missouri became known as the Lead Belt.

Mining was the lifeblood of these small towns, and the industry drew a flood of immigrant workers, many from Hungary. These men took on the most grueling and dangerous jobs, often working as shovelers deep in the mines. Locals derogatorily called them “hunkies” and paid them a measly thirty cents an hour for backbreaking labor.

The Lead Belt community hardly welcomed their presence.

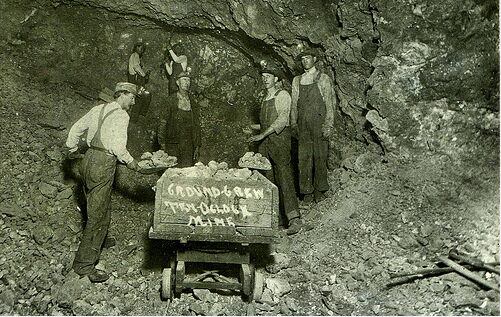

Pictures above Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri

The Lead Belt Riot of 1917: Fear Turns to Violence

By 1917, tensions between immigrant miners and local laborers had reached a boiling point. World War I fueled a wave of xenophobia, and many viewed Hungarian miners as foreign threats, making them easy scapegoats.

Then came the riot.

On July 14, 1917, a mob of American miners, waving American flags, stormed the homes and boarding houses of Hungarian workers. They looted, beat, and chased them out of town.1Macon Chronicle-Herald – Fri, Jul 20, 1917 | Pg 1 Newspapers at the time described the event bluntly:

“Flat River Miners Eject Foreigners.”

But not all of those forced to flee were foreigners. Many were naturalized American citizens, legally entitled to live and work in the Lead Belt. In their desperate escape, some left behind everything—homes, businesses, even their wives and children. The violence was so extreme that Hungarian-American organizations called for a congressional investigation, demanding answers from Washington about how such an event could happen on U.S. soil.

Years of Rising Tensions

The 1917 riot wasn’t an isolated event—it was the violent climax of years of tension. As early as 1913, company officials and anti-union groups targeted Hungarian, Bohemian, and Italian miners for their union activities. The situation turned deadly when mining company guards opened fire on striking workers, injuring two and escalating the conflict into a near-militarized standoff.

In response, 500 miners blockaded the mines, stopping and searching vehicles to prevent strikebreakers from getting through. What happened in the Lead Belt was part of a broader pattern of anti-immigrant violence across the country, but it left a lasting mark on the people—and the folklore—of Missouri. By 1917, these tensions had already boiled over once before. Just four years earlier, the Lead Belt saw gunfire, barricades, and a full-scale labor war.

The same fears that fueled those clashes—fears of foreign workers taking jobs and gaining power—escalated into violence. Rioters didn’t stop at homes—they dragged Hungarian workers into the streets, beat them, and set fire to their belongings. Rioters looted businesses, destroyed shops, and drove entire families to flee with only what they could carry. By the time it ended, mobs had herded over 700 Hungarian miners onto trains, exiling them from the very town they helped build. As violence spiraled out of control, state officials sent the Missouri State Militia to restore order. Soldiers patrolled the streets of Flat River, but their presence wasn’t just to stop further rioting—it was to ensure that the mass expulsion of Hungarian miners remained permanent.

The Aftermath of Expulsion

By the time the dust settled, many of those forced onto trains would never return. Some, like a Russian immigrant and his family, barely survived the journey. After mobs drove him to St. Louis, he returned to salvage what remained of his home—only to receive a telegram informing him that exposure had killed two of his children.The riot hadn’t just displaced people. It had killed them.

Women didn’t just stand by during these clashes—they fought, too. In one 1913 incident, a female striker nearly attacked a company lawyer with a rock, a visceral reminder that these weren’t just labor disputes; they were full-scale community struggles.

The High Cost of Striking

The strikes weren’t just violent—they were financially devastating. With a large portion of their workforce gone, several mining operations slowed or shut down completely, costing the region over $100,000 a day in lost wages and damages. The Lead Belt depended on its mines, and now, thanks to fear and violence, the industry itself was beginning to collapse.

Some merchants even refused to extend credit to striking miners, effectively starving them out to force them back to work. Desperation, distrust, and fear of outsiders — the perfect storm for a legend to be born.

The Vampire of Elvins

Between 1910 and 1920, an unsettling number of children in the area died. In an era before vaccines and antibiotics, disease took many young lives, and in 1917, a diphtheria outbreak devastated the region. But medical explanations didn’t always satisfy a grieving community looking for someone—or something—to blame.

Soon, a rumor began to spread.

A Hungarian miner living in Elvins was accused of being a vampire. Locals whispered that he lured children to his home… and ate them. Depending on who told the story, the man was also said to be an albino, his skin deathly pale, his hair bone-white, and his eyes red as blood.

When he died, the townspeople refused to let him be buried among their dead—especially not near the children’s graves. Instead, his body was placed at the far edge of Gibson Cemetery, enclosed by a wrought iron fence lined with crosses. The belief? Even in death, the barrier would keep him from rising from the grave.

Unlike many urban legends, this one had a physical marker. The wrought iron fence was real. The crosses, placed to prevent his return, were real. And according to local records, his grave was surrounded by the small headstones of children—further fueling the belief that he had preyed upon them in life.

And from there, the legend of the Vampire of Gibson Cemetery was born.

Folklore, Fear, and the Power of Stories

Was there really a vampire buried in Gibson Cemetery? Of course not. The accused man was just another immigrant caught in the crossfire of prejudice and paranoia.

And the dead children? They died of disease, not supernatural horror.

But history has a way of shaping legends. In 1917—the same year the Lead Belt Riot erupted—the Washington Times ran a full serialization of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In a town already primed with anti-immigrant fears and real-life violence, it’s not hard to imagine how the folklore took hold.

A foreigner. A pale-skinned outsider. A town full of frightened people looking for someone to blame.

A vampire was the perfect monster.

Gibson Cemetery Today

Today, Gibson Cemetery has been swallowed by time, its iron fences rusted and its gravestones shattered. No one knows exactly where the so-called vampire was buried, but it is rumored he was buried within the cast iron fence. Maybe he’s still out there, hidden beneath the overgrowth, his grave forgotten.

Or maybe he was never there at all—just a name lost to history, twisted into a monster by fear.

Either way, the legend remains. And in a place like this, some stories never stay buried.